Birthplace of the Asian American Movement

In 1968 Emma Gee (Chinese American) and Yuji Ichioka (Japanese American) were UC Berkeley doctoral students living together on Hearst Avenue. They were active participants in the progressive political and social movements of the day and dreamed of an organization and identity that would bring people of different Asian heritages together in common action and purpose. To this end, they invited a number of activists to meet at their home. The result was the establishment of the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA). This was the invention and first use of the term Asian American. Soon the phrase was understood not only as an organizational name, but also as a personal and political identification and the definition of a scholarly concept and discipline.

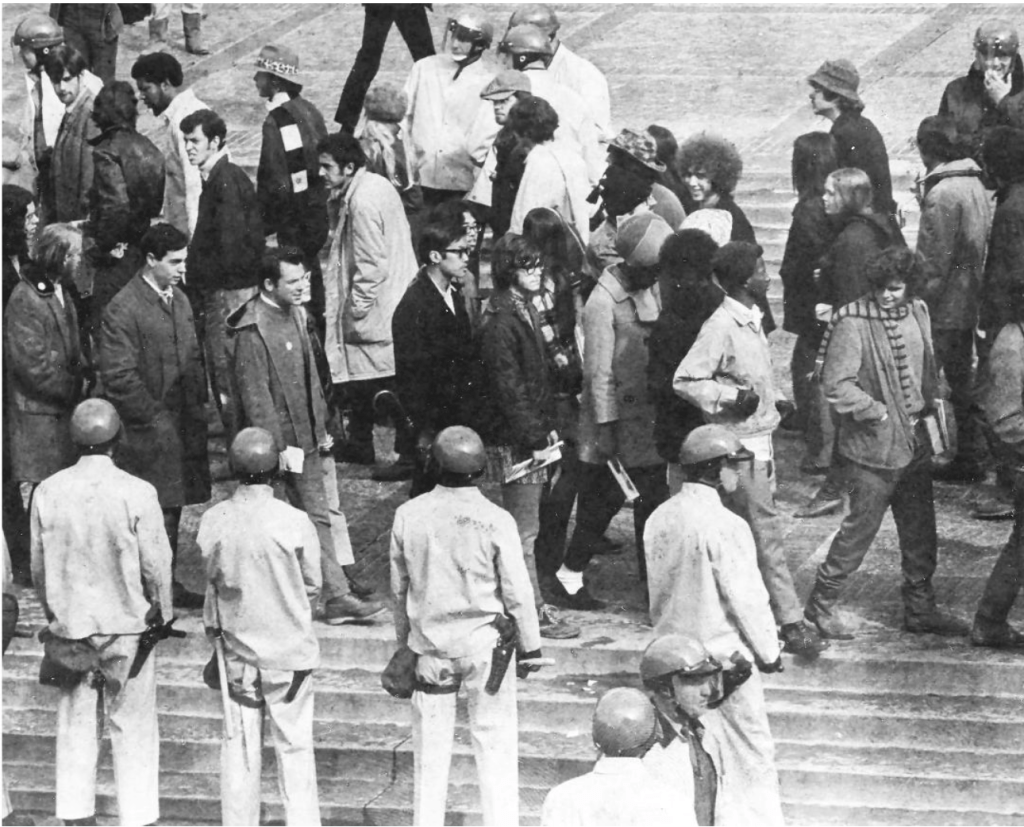

The AAPA was part of the leadership of the massive 1968-69 Third World Liberation Front student strikes aimed at creating community-based ethnic studies programs at San Francisco State and UC Berkeley. When Berkeley established the nation’s first Ethnic Studies Department in 1969, Asian American Studies was a core discipline and has remained so ever since. Scores of other institutions have similar programs, and the federal government even recognizes May as Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

Gee and Ichioka, who eventually married, had distinguished careers teaching and publishing in the field. After Ichioka’s death in 2002, the UCLA Asian American Studies Center established the Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee Endowment in their honor. The City of Berkeley recognizes the couple’s former home at 2005 Hearst Avenue as an historical landmark, accurately describing the house as the “Birthplace of the Asian American Movement.”

Chancellor Tien and the Fall of Affirmative Action

Dr. Chang-Lin Tien was UC Berkeley’s first Asian American chancellor, serving from 1990 to 1997. Born in China in 1930, he and his family moved to Taiwan in 1949 to escape the mainland Communist victory. Tien completed his graduate education in engineering in the United States and eventually obtained American citizenship. He joined the UCB Mechanical Engineering Department as a faculty member in 1959 and excelled as both a teacher and researcher. He served as department chair and as vice chancellor before being appointed chancellor in 1990. His friendly, outgoing personality made him a popular figure on campus. He successfully raised large private contributions for the university and was particularly recognized for his strong support for UCB’s affirmative action policy. That policy allowed for the admission of promising students from “under-represented minority groups,” even though their GPAs and test scores might have been lower than Asian and white applicants who were denied admission.

Dr. Chang-Lin Tien was UC Berkeley’s first Asian American chancellor, serving from 1990 to 1997. Born in China in 1930, he and his family moved to Taiwan in 1949 to escape the mainland Communist victory. Tien completed his graduate education in engineering in the United States and eventually obtained American citizenship. He joined the UCB Mechanical Engineering Department as a faculty member in 1959 and excelled as both a teacher and researcher. He served as department chair and as vice chancellor before being appointed chancellor in 1990. His friendly, outgoing personality made him a popular figure on campus. He successfully raised large private contributions for the university and was particularly recognized for his strong support for UCB’s affirmative action policy. That policy allowed for the admission of promising students from “under-represented minority groups,” even though their GPAs and test scores might have been lower than Asian and white applicants who were denied admission.

Some Chinese American parents vehemently opposed the policy, believing it discriminated against their high-achieving children who were often steered to UC campuses that were less prestigious than Berkeley. However, opposition to affirmative action was not unanimous in the Chinese American community. Especially on campus, many students and faculty of Chinese descent joined Tien in strongly backing the policy. But the parents’ well-organized and highly publicized campaign attracted substantial public attention and the support of prominent California Republicans, including UC Regent Ward Connerly. In 1995 Connerly persuaded the Board of Regents to end the university’s affirmative action policy. In 1996 he and his friend and patron Republican Governor Pete Wilson strongly backed Proposition 209, a voter initiative that effectively banned affirmative action in all California state and local government operations, including public education.

Many media sources reported that Tien’s 1997 resignation was in part due to his deep disappointment over the defeat of affirmative action. Chang-Lin Tien died in 2002, ending a distinguished academic career of more than four decades. On campus he is memorialized by the Chang-Lin Tien Center for East Asian Studies.

Eastwind Books

In 1996 Beatrice and Harvey Dong bought Eastwind Books, a store specializing in Asian and Asian American literature. The store had opened in San Francisco fifteen years earlier and subsequently relocated to Berkeley. It moved to 2066 University Avenue in 1998. The Dongs were longtime community activists.

In 1996 Beatrice and Harvey Dong bought Eastwind Books, a store specializing in Asian and Asian American literature. The store had opened in San Francisco fifteen years earlier and subsequently relocated to Berkeley. It moved to 2066 University Avenue in 1998. The Dongs were longtime community activists.

Harvey was an early member of the Asian American Political Alliance and an enthusiastic participant in the 1969 Third World Liberation Front strike. He later returned to the university to earn a Ph.D. in Ethnic Studies and now teaches part-time in that department.

Beatrice was in the Asian American Studies program as an undergrad and continued her activism after graduation, even though she was paralyzed by a freak gunshot incident in the 1980s.

The Dongs made Eastwind into a significant community institution, championing Asian American writers, sponsoring author talks and other events, and even starting a publishing program. Because of its importance to the community, there was shock and sadness when Harvey Dong recently announced in 2023 that the store was closing. Ironically, its last day was April 30, the opening day of this exhibit.

But the Dongs have assured the community that they will continue to sell books online, sponsor events, and maintain the publishing program. And Harvey will continue to teach at the university. Eastwind will no longer have a physical presence in Berkeley, but it will remain a part of the city’s rich political and cultural environment.

“I am Proud of My Chinese Heritage”

Carolyn Gan from “A Brief History of the Chinese Chapter of the California Alumni Association” (YouTube)

“The East Asian library was something we all wanted, and the Chinese Alumni Club of the 1960s––the group that came after us––had even bigger dreams. I think in our own hearts, we always wanted that Asian library––to let the rest of the world know how great the Chinese heritage is. That’s it––when we were young, we were taught to be humble: ‘Don’t look at anybody in the eye.’ You walk around with your head almost bowed to people!

“But now, I think we should stand up straight. I am proud of my Chinese heritage …. Cal really had a truly democratic spirit about it—I don’t think other schools can compete with Cal. I think the world is better because of the interchanges we have and the University of California certainly was a big promoter of it. So, I think it is getting to be a better world through education and through the activities that we have here.

Ying Lee (1932-2022)

Ying Lee was the first Asian American member of the Berkeley City Council, serving from 1973 to 1977. Born in China in 1932, she came to San Francisco with family members as a refugee fleeing the Japanese military occupation of her homeland during World War II. She graduated from San Francisco public schools and earned a BA and MA at UC Berkeley. In the 1950s she was elected Miss Chinatown and hung out with Beat Generation poets and writers. In the 60s she married Cal mathematics professor John Kelly and began teaching at Berkeley High.

It was also in the 60s that Ying became passionately involved in progressive politics, as an anti-war activist and civil rights advocate. She was elected to the city council on a leftist slate of candidates and served alongside Loni Hancock. In 1975 Ying ran as the left candidate for mayor but was defeated by Warren Widener, the moderate incumbent. She worked several years on the staff of Congressman Ron Dellums and, after his retirement, as the first legislative director for his successor, Barbara Lee. In her later years, Ying served on the boards of the Asian Law Caucus and Asian Health Services and was a prominent member of Grandmothers Against the War.

Ying Lee remained an activist right up to her passing, surrounded by family and friends, at age 90 in 2022. The Berkeley Historical Society published her oral history in 2012. It was reissued in 2022 and is available for sale at the museum. It’s the story of an extraordinary life very well lived.

1965 to Present: New Politics, New People

The 60s and early 70s were a time of social and political change in the US, and no northern city was more affected by this process than Berkeley. Some Chinese American students and residents marched in protests and demonstrations, while many others remained on the sidelines. All benefited from new state and federal civil rights legislation. But the law that most dramatically affected the Chinese American experience was the 1965 reform of American immigration policy. It replaced the old, heavily biased national quota system with much fairer criteria. For the first time since 1882, immigration applicants from Asia had equal status with those from Europe. After the 1965 reform, immigration from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore to Berkeley and its university grew significantly. After the fall of Saigon, Vietnamese of ethnic Chinese background joined these immigrants.

During the 1970s, the Chinese government initiated economic reforms that culminated in the adoption of a semi-capitalist system after the ascension to power of Deng Xiaoping in 1978. The country established new contacts with the rest of the world, including diplomatic relations with the United States. Universities reopened. These changes created the possibility for Chinese students to attend American colleges and for significant general immigration to the US.

Berkeley and its university were affected by these new opportunities to come to America. Asian population grew from about 7% of Berkeley’s population in 1970 to more than 20% in 2020, and most of the latter were people of Chinese descent. The Cal student body was overwhelmingly white in 1970, but by 2020 42% of the university’s undergrads were Asian, again a majority of them of Chinese heritage. Most probably had immigrant parents, and while many came from educated backgrounds, some were the first in their family to attend college. UC Berkeley became an important engine of social and economic mobility, allowing many Chinese who had “touched ground” in the Bay Area to put down deep roots.

- By Charles Wollenberg.