Introduction

The University of California at Berkeley undoubtedly played a role in the early history of the Chinese community in Berkeley. Some scholars have argued that one reason why the US allowed Chinese students to come even during the exclusion period is that it was in return for China allowing American Protestant missionaries to work in China. The University saw itself as a place where the best Chinese would come and study. In 1901, UC adopted a plan to take on “the role of educator of the gigantic empire. It is meant to make the University the tutor of China.”[1] Chinese students would be “imbued with Western learning and ideas and civilization, to return to China and radiate these influences throughout the empire.” The program began with eight students enrolled for the 1901 academic year. The following year 15 Chinese students were enrolled at the University, in which all but one were Cantonese.[2]

In 1901, Chinese students at UC formed the Chinese Student Alliance. Within a few years, it became a national organization. Students at UC began publishing the Chinese Student Alliance of America in 1905, which became the official publication of the student organization.

Among the Chinese studying at UC Berkeley was the son of Sun Yat Sen, Sun Fo, who graduated in 1916 with a B.A. in the College of Letters and Sciences. Later, Sun Fo would become a high-ranking official in the government of the Republic of China.

Dr. Kiang Kang-hu (1883-1954). A colorful and historic figure in the history of the Chinese socialist movement, Kiang Kang-hu, taught Chinese languages and civilization at the University between 1914-1920. He also donated about 10,000 books to the University that became the cornerstone of its collection of Chinese literature.

The books Kiang donated had been in his family for generations and survived the Boxer Rebellion.[3] Kiang later collaborated with the American poet Witter Bynner on the translation of T’ang Dynasty poetry, a project that in 1929 culminated in the publication of the book The Jade Mountain: A Chinese Anthology, Being Three Hundred Poems of the T’ang Dynasty, 618-906.

[1] The Berkeley Gazette, August 9, 1901, p.8; [2] Ibid, September 12, 1902, p.2; [3] See the Boxer Indemnity Fund

Boxer Indemnity Fund

The 1899-1901 revolt of an anti-foreign Chinese group known as the Boxers resulted in eight nations, including the U.S., providing military support to quell the rebellion. With the defeat of the Boxers, the Chinese government agreed to pay reparations to the foreign nations, including an amount to the U.S. $17,000,000 in excess of our demand. President Roosevelt led the establishment of a scholarship program to make use of that amount rather than simply pocketing the money or returning it directly to China. The Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program began in 1909 to educate Chinese students in U.S. universities.

president of the Republic of China Zhou Ziqi is seated in the front center. (Wikipedia)

Students were selected following stringent examination in China; below

left is a letter of recommendation for a prospective Cal student in 1915:

Blue & Gold yearbook, 1917

Lynne Lee Shew was admitted

to UC and graduated in 1917

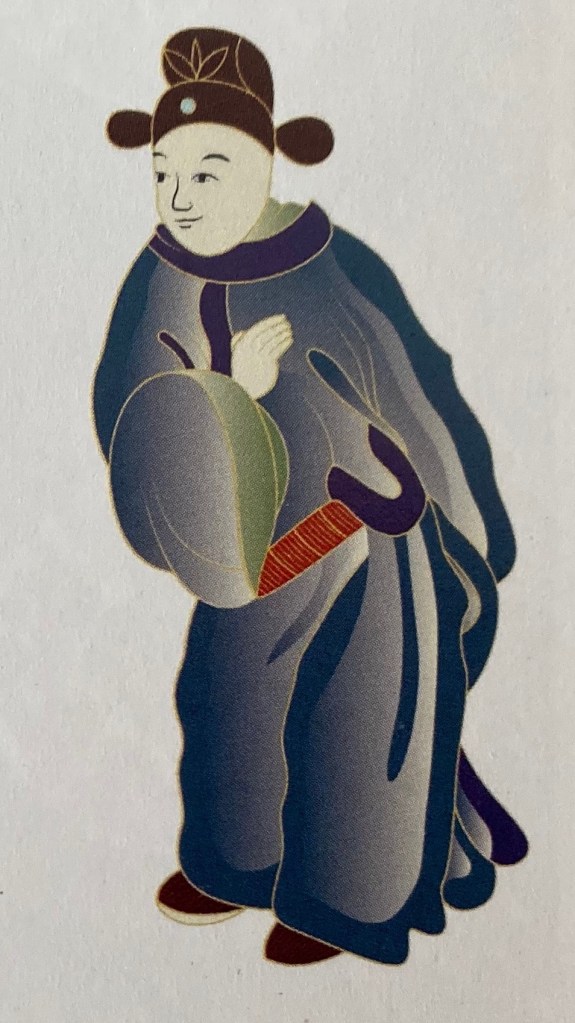

The Chinese Students Club

The Chinese Students Club, established in 1913, first appeared in the Blue & Gold yearbook in 1920. Its stated purpose (in 1960):

The Chinese Students’ Club offers a cultural and social agenda. To help the Chinese student to become adjusted to University life is the purpose of the organization.

The Club ceased operating in 1966

In the 1920 Blue & Gold Lynne L. Shew is listed among the graduates (but not pictured). Yuen R. Chao, who would become a faculty member (see his story below), is listed among the graduates with his photo top left.

Yuen Ren Chao -趙元任 – (1892-1982)

Linguist and phonologist

“I am a Modern Man”

Born in Tianjin, China, in 1892, Yuen Ren Chao came to the US in 1910 as part of the Tsinghua University‘s Boxer Indemnity Fund, first for undergraduate study at Cornell University, where he got a BSc in mathematics in 1914, and then in a graduate program at Harvard, where he got a Ph.D. in philosophy in 1918.

Born in Tianjin, China, in 1892, Yuen Ren Chao came to the US in 1910 as part of the Tsinghua University‘s Boxer Indemnity Fund, first for undergraduate study at Cornell University, where he got a BSc in mathematics in 1914, and then in a graduate program at Harvard, where he got a Ph.D. in philosophy in 1918.

Chao went back to China in mid 1920s and taught at Tsinghua University. He was now in his late twenties and early thirties. His future wife, Buwei Yang, upon their first encounter describes him as “A young man dressed in shabby western clothes.” She herself, a Japan-educated gynecologist, is dressed in western clothes. Both are “new-style” people. By that time Chao, who is now more interested in linguistics, has already translated into Chinese “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” and composed the music for one of the favorite Chinese songs “Teach Me How to Miss Him.” He is a great punster: “If you have nothing to say, Don’t say it well.”

For a while, he is interpreting for the prominent British philosopher Bertrand Russell and his partner, feminist, socialist and author Dora Black. He shares a house with them and like them, according to Buwei, he wants “to put every tradition and institution under critical doubt.”

When Yuen Ren and Buwei marry in 1921, a newspaper announces “New-style Wedding of New-Style People.” There is to be no reception and “absolutely no gifts, except in the form of letters, literary or musical compositions or contributions to the Science Society of China.”

Chao is indeed “a modern man”: for the next twenty years, in China and in the US, he is engaged in unifying Chinese language, by developing a model for spoken Mandarin, or p’u t’ung hua, which is still followed in China. He is pioneering audiolingual methods of teaching.

In 1936 Chao writes a poem

How Can I Not Think of Him

There are some clouds in the sky and a breeze on the ground Ah! The breeze blew my hair and taught me how not to miss him? The moonlight falls in love with the ocean The ocean is in love with the moonlight Ah! Such a honey-like silver night teaches me how to miss him? The falling flowers on the surface of the water flow slowly, And the fish under the water swim slowly Ah! Swallow, what did you say? Teach me how to miss him? The dead trees arc shaking in the cold wind Wildfires are burning in the twilight Ah! There are still some children in the west Can you teach me how to miss him?

How Can I Not Think of Him becomes a classic of the Chinese 20th century music after Chao composes and performs a song set to the poem.

In 1938, after the Japanese invasion of China, Chao and family, by now he and Buwei have four daughters, sailed to Hawaii.

After teaching at Yale and Harvard, Chao came to UC Berkeley in 1947. He was 55 years old. Students loved to work with him. In 1960, he was elected president of the American Oriental Society. Professor Chao retired in 1962.

Yuen and Buwei live on Cragmont Ave. They are known for their open house. Jean Thomas, who stays with them for three months, remembers how the Juilliard Quartet plays at the Chaos’ house one weekend. Many restaurant owners know him well.

Family home on Cragmont Ave., Berkeley, 2023 photo

Chao’s wife, Buwei Yang Chao, was 48 years of age when she wrote her autobiography in 1947. Buwei claimed that she was a ‘typical’ Chinese woman with ‘unusual experiences.’ ‘Typical’ because, in her words: “I grew up in a big family of four generations living in the same house [of 128 rooms]. I was taught to read and write at home. I learned later to cook and sew.” But she was also ‘unusual’: “I broke my engagements at a time when engagements were never broken. I was principal of a school before I went to college. I joined revolutions and took refuge from wars. I healed grownups and brought a few hundred children into the world.”

In 1973, when 81-year-old Chao and wife visited China, he was invited to meet with Zhou Enlai, the first premier of the People’s Republic of China. Chao died in 1982 at the age of 89.

In contemporary China, Chao is revered as the great pioneer in literary and language reform. When one enters the main lobby of Tsinghua University, Chao Yuen Ren is featured among the Four Greats. He also commands great respect in his private life: a recent documentary in China focuses on Buwei Yang and Yuen Ren Chao, these two “new-style” people who lived together for more than six decades.

Shih Hsiang Chen – 陈世骧 – (1912-1971)

Chinese literature

SHIH-HSIANG CHEN was born in Peking in 1912. In China, he taught first at

Peking University and then at National Hunan University, coming to the US in

1941 to study and teach at Harvard and Columbia. He joined the faculty at UC

in the Department of Oriental Languages in 1945, where in 1948 he authored

“Literature, As Light Against Darkness,” a study of the medieval poet Lu Chi’s

“Essay on Literature.” He died in 1971: from his obituary “. . . a clear young

voice raised in an ancient folksong, to delight the friends who loved him and

who made the house on Highgate the gracious setting for the poem which was

his life.”

Shiing Shen Chern – 陳省身 – (1911-2004)

Mathematician and geometer

Shiing Shen Chern is universally acknowledged as the Father of Differential Geometry and one of the great mathematical minds of the 20th century. Chern was born in Xiushui, Jiaxing, China in 1911. He got his Bachelor’s Degree at Nankai University, Tianjin in 1930 and then spent four years at Tsinghua University, receiving a Master’s in mathematics.

Shiing Shen Chern is universally acknowledged as the Father of Differential Geometry and one of the great mathematical minds of the 20th century. Chern was born in Xiushui, Jiaxing, China in 1911. He got his Bachelor’s Degree at Nankai University, Tianjin in 1930 and then spent four years at Tsinghua University, receiving a Master’s in mathematics.

From 1934 to 1936, Chern studied in Germany at the University of Hamburg and received a Doctor of Science degree in mathematics.

Back in China, Chern spent 1937-1943 at the Tsinghua University. His future father-in-law was a professor of mathematics there. He often invited Chern to their house parties, where he met his future wife.

In 1939, Chern married Shih Ning Cheng. The couple eventually had two children, Paul and May.

From 1943-45 Chern was in the US, where he did research at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. Chern returned to China after the war[2] where he remained from 1946-1948. Back to the US in 1949, he taught at the University of Chicago.

Chern came to UC Berkeley in 1961. According to Professor Yau, a Fields Medal recipient (the highest possible award in mathematics), whose dissertation advisor was Chern: “While at Berkeley, Chern had hired many outstanding geometers and topologists who set up Berkeley to be the center in geometry and topology.” “The graduate students felt as if they were in the center of the universe of geometry. Everyone else in the world of geometry came to visit.” Apart from doing brilliant research, Chern trains many outstanding students. This group includes Yau, Garland, do Carmo, Shiffman, Weinstein, Banchoff, Millson, S. Y. Cheng, Peter Li, Webster, Donnelly, and Wolfson. In 1979, Chern stops teaching, but doesn’t retire from the world of math. In 1981, he cofounds and becomes the first director of the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute (MSRI) in Berkeley.

Chern was known to be irresistible socially: “Because of his pleasant personality and vast knowledge of Chinese culture and history, he naturally attracted everyone around him.” “It is well known that Chern treated every visitor with a splendid dinner in a Chinese restaurant or else an elegant party in his [El Cerrito] house,” recounts Yau. “He easily made friends with chefs, waiters/waitresses, and owners of restaurants, especially the Chinese restaurants.”

The Institute was founded in 1982 and Chern was the cofounder and the founding director of the Institute

Chern didn’t forget his roots. From the opening of relations with China in 1973, he regularly visited his birth country. In 1985 he established Nankai Institute for Mathematics (NKIM) at his alma mater, now called Chern Institute for Mathematics.

In 1999 Chern moves back to China permanently. He dies in Tianjin in 2004 at the age of 93. Colleagues remember him “as the soul of modesty.” “Despite becoming the grand old man of Chinese mathematics, he remained modest and unassuming, always willing to listen and to encourage the young.” The Chern Institute at Nankai is a lasting tribute to his role in revitalizing Chinese mathematics.

Chern remains a legendary figure in China. It is not surprising then that the Chinese astronomers named a star after Shiing Shen Chern.

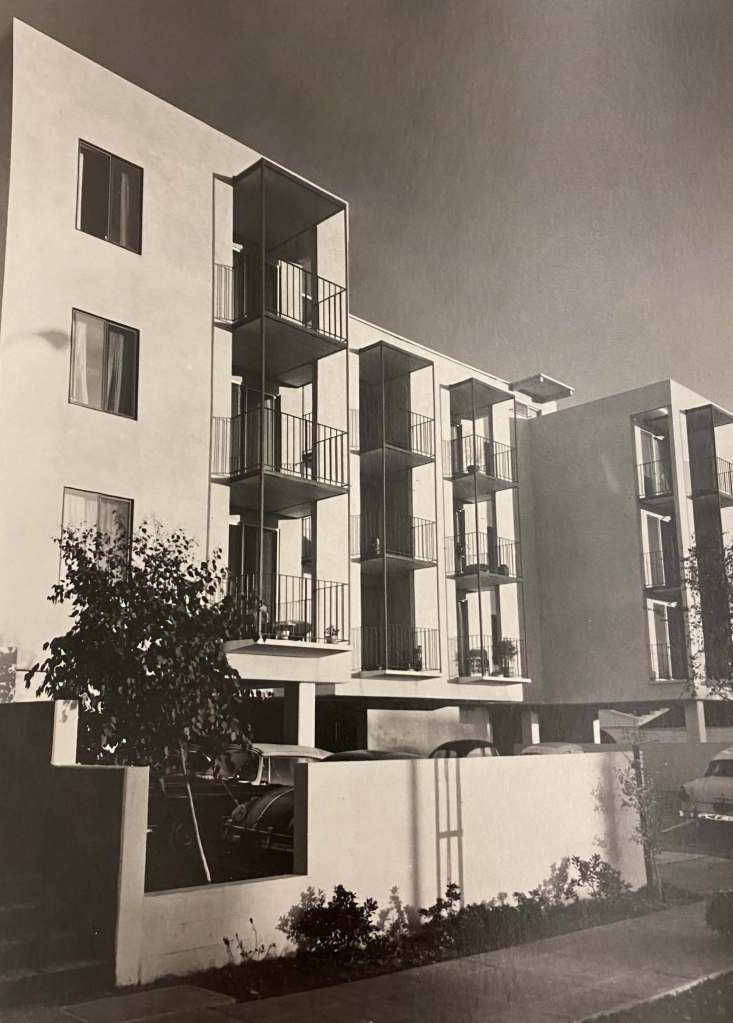

Roger Lee (1920-1981)

Architect

Roger Lee, renowned Berkeley architect, graduated from the University of California with a B.A. in Architecture, with highest design honors, in 1941. He was in private practice as an architect in Berkeley from 1949 to 1970, winning numerous awards and honors. He taught as a Lecturer in the UC Extension and in the Department of Architecture at UC from 1959 to 1961.

Roger Lee, renowned Berkeley architect, graduated from the University of California with a B.A. in Architecture, with highest design honors, in 1941. He was in private practice as an architect in Berkeley from 1949 to 1970, winning numerous awards and honors. He taught as a Lecturer in the UC Extension and in the Department of Architecture at UC from 1959 to 1961.

Among his notable buildings in Berkeley are the Chinese Community Church, the former Vim & Vigor Restaurant and Thos Tenney Record, Sound & Music Shop, several homes and many apartment buildings.

Choh Hao Li – 李卓皓 – (1913-1987)

Biologist

CHOH HAO LI, born April 21, 1913 in Guangzhou, China, touched ground in Berkeley as a UC doctoral student in 1935, leaving the Nanjing University to remain here for the rest of his life. He joined the staff at Berkeley’s Institute for Experimental Biology in 1938, where he launched a career focused on the human pituitary growth hormone, discovering its 256 amino acids and becoming the first to synthesize the hormone. As a professor at Cal from 1950 to 1967 and thereafter at UCSF until his retirement in 1983, Li maintained his focus on pituitary gland hormones. He was honored with over 25 scientific awards and 10 honorary degrees. Choh Hao Li died November 28, 1987, at the age of 74.

CHOH HAO LI, born April 21, 1913 in Guangzhou, China, touched ground in Berkeley as a UC doctoral student in 1935, leaving the Nanjing University to remain here for the rest of his life. He joined the staff at Berkeley’s Institute for Experimental Biology in 1938, where he launched a career focused on the human pituitary growth hormone, discovering its 256 amino acids and becoming the first to synthesize the hormone. As a professor at Cal from 1950 to 1967 and thereafter at UCSF until his retirement in 1983, Li maintained his focus on pituitary gland hormones. He was honored with over 25 scientific awards and 10 honorary degrees. Choh Hao Li died November 28, 1987, at the age of 74.

Choh Hao’s wife Shen-hwai Lu (Annie) designed their home at 901 Arlington Ave., where they raised a family.

All three children attended Berkeley public schools, graduating from Berkeley High School.

T. Y. Lin – 林同棪 – (1911-2003)

Engineer, ‘Father of Prestressed Concrete’

Tung Yen Lin was born in Fuzhou, China in 1911 to a well-educated family—his father was a judge who studied at Yale University, and several of his cousins studied at Tsinghua University. Lin benefited from the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program[1]. He studied at UC Berkeley in 1931 and in two years received a master’s degree in civil engineering. According to Lin: “America was the country that gave back their restitution[1] to educate People. That created a lot of good will.”

Tung Yen Lin was born in Fuzhou, China in 1911 to a well-educated family—his father was a judge who studied at Yale University, and several of his cousins studied at Tsinghua University. Lin benefited from the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program[1]. He studied at UC Berkeley in 1931 and in two years received a master’s degree in civil engineering. According to Lin: “America was the country that gave back their restitution[1] to educate People. That created a lot of good will.”

In 1933 Lin was back in China, where he was hired by the Chinese Ministry of Railway; at the age of twenty-five he became the chief bridge engineer of Chongqing-Chengdu railway, with the responsibility for the survey, design and construction of more than 1,000 bridges throughout China.

Soon Lin meets Margaret Kao, whose father is a judge in Kunming where she is studying at the university. They marry in 1941. Their son Paul is born in 1942. In 1946, the family arrives in the US, where Lin comes to teach at the University of California at Berkeley. Their daughter Verna is born soon after.

While teaching at UCB, Lin became interested in the idea of prestressed concrete. He went to Belgium in 1953, for one year, where he worked at the Magnel Laboratory, University of Ghent. “I learned a lot of theory and actual action of all those prestressed concrete elements in that laboratory.” While in Belgium he wrote a book, Design of Prestressed Concrete Structures, translated into many languages and prestressed concrete becomes a revolution in construction. With one of his students, Lin establishes a company, “T.Y. Lin Associates” in Los Angeles and eventually all over the world. Lin enjoyed teaching at UC Berkeley: ‘My teaching was successful in a way because I teach it from the heart.”

Family life is also going well. Among other things, T.Y. and Margaret take dance lessons together at Arthur Murray Studio. Their house in El Cerrito, designed by Lin as the world’s first residential structure made of prestressed concrete, features a 1,000 sq feet dance floor. T.Y. jokes about the good relationship between him and Margaret: “the best husbands are either an engineer or a professor. So, I qualify for both.”

8701 Don Carol Drive, El Cerrito

Lin retired from teaching in 1977 but was active all over the world in bridge design at the T.Y. Lin International company. Going back to China was very attractive to Lin. When the US and China reestablished their relationship in the mid 1970s, Lin traveled to China several times and was instrumental in building bridges in Shanghai across Hwang Pu River and developing the Pudong area of Shanghai, now the renowned financial center of the city.

T.Y. Lin passed away in 2003 in El Cerrito. He remains a legend and a visionary in the US and in China. To this day, T. Y. Lin International is one of the premier bridge-building companies in the world, involved in the recent rebuilding of the Bay Bridge.

[1] See “Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Fund,” lower left on this wall

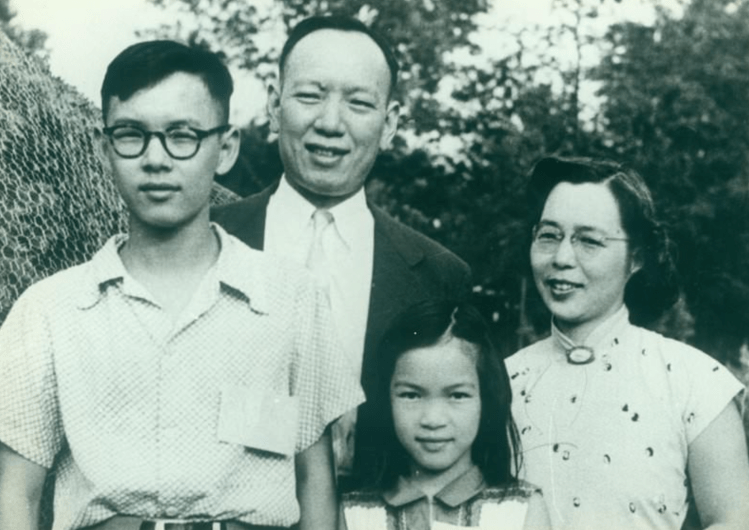

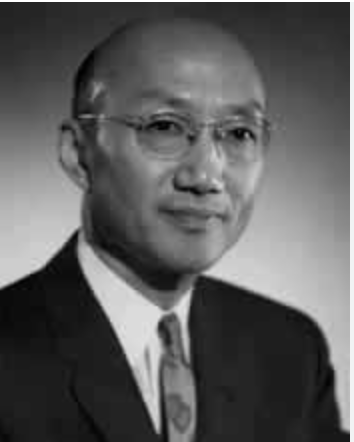

Chang-Lin Tien – 田長霖 – (1935-2002)

UC Berkeley Chancellor, 1990-1997 Microscale Thermophysical Engineering

Chang-Lin Tien was born in 1935 in Wuhan, China. The sixth of eight children, Tien grew up in the tumultuous setting of China of the 1930s and 40s. Amongst war and revolution, his family alternated from elite comfort to refugee status. His father was educated at Peking University and was a city assessor, then banker, and the family were well off. But in 1949, at the end of the civil war, the family fled to Taiwan as refugees. Tien was pursuing his Bachelor of Science degree at National Taiwan University when his father passed away in 1952. “My family … became very poor in many ways.” Looking for a scholarship in the US that could pay for board and tuition, Tien ended up in a Masters in mechanical engineering at the University of Louisville. He continued at Princeton University in a Ph.D. program: “I was so poor. When I first went to Princeton I lived in an attic. I couldn’t even stand up because of a very low ceiling, but it was inexpensive; that’s why I went there.” Writing home to the love of his life, Di-Hwa, in Taiwan helped: “We would always write air letters. It was much cheaper. I remember it was only five or ten cents for international air letters at that time, but still it was expensive for me. We wrote almost two or three times a week.”

Chang-Lin Tien was born in 1935 in Wuhan, China. The sixth of eight children, Tien grew up in the tumultuous setting of China of the 1930s and 40s. Amongst war and revolution, his family alternated from elite comfort to refugee status. His father was educated at Peking University and was a city assessor, then banker, and the family were well off. But in 1949, at the end of the civil war, the family fled to Taiwan as refugees. Tien was pursuing his Bachelor of Science degree at National Taiwan University when his father passed away in 1952. “My family … became very poor in many ways.” Looking for a scholarship in the US that could pay for board and tuition, Tien ended up in a Masters in mechanical engineering at the University of Louisville. He continued at Princeton University in a Ph.D. program: “I was so poor. When I first went to Princeton I lived in an attic. I couldn’t even stand up because of a very low ceiling, but it was inexpensive; that’s why I went there.” Writing home to the love of his life, Di-Hwa, in Taiwan helped: “We would always write air letters. It was much cheaper. I remember it was only five or ten cents for international air letters at that time, but still it was expensive for me. We wrote almost two or three times a week.”

In 1959, Di-Hwa arrived in the US, and the couple got married. Tien joined the UC Berkeley faculty as acting assistant professor in mechanical engineering the same year. Finding an apartment to rent close to the engineering department on the north side of campus wasn’t easy: “The rental listings said ‘No Negroes, no Orientals’ in those areas…. At that time on the north side, it was all exclusive of Negroes and Orientals, as they called it…. They said that I had to go to the southwest of Berkeley, west of Shattuck and south of Dwight or Ashby. Or further west, west of Sacramento.” In 1964, Tien got tenure at the age of 28. As a young professor he was supportive of the Free Speech Movement that erupted on campus: “I came as a poor student, penniless, suppressed in many ways, disadvantaged, so I always was on their side.” Tien specialized in the field of heat and mass transfer and became a world-known specialist in the field; he recalled that many “prominent heat transfer people either were my students or my postdocs in my lab.”

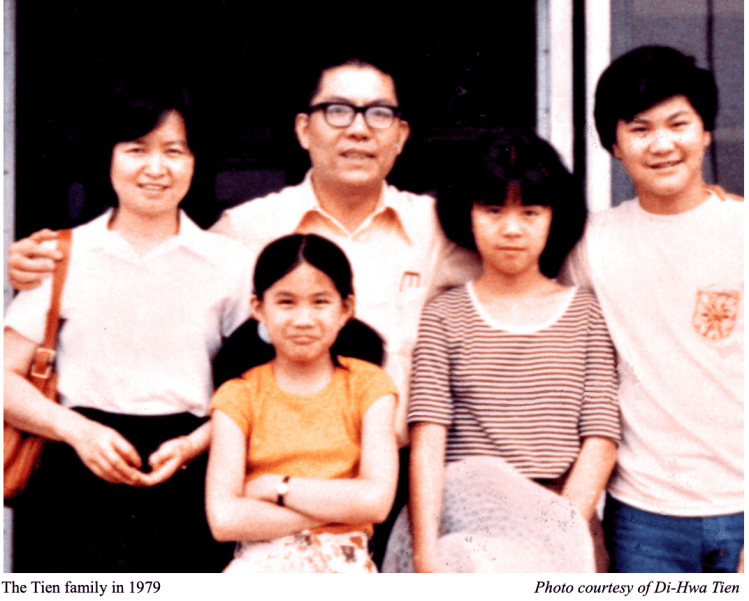

His personal life was thriving as well, with three children born by the early 1970s, who eventually all got to travel all over the world, accompanying their father.

On campus, Tien was loved by the students, but also active in the campus affairs.

In the Academic Senate, he was chairman of the Status of Women and Minorities, called SWIM. He recalled: “We organized many groups, tried to help underrepresented minorities.” From 1990-97, Tien served as UC Berkeley Chancellor. In his oral history he reiterated his guiding philosophy: “No issue really makes me unacceptable to different groups. They all generally trust me, although I don’t satisfy necessarily all their demands, but you have to try to find a way to help all sides.”

Tien passed away in 2002 of a stroke at the age of 67. Many would whole-heartedly agree with the words his son Norman chose to describe his father as “a person of great strength with a drive and energy to make the world a better place in which to live, and who was able without fear to stand by his principles.”

- By George O. Petty and Tonya Staros; 2023 house photos by George O. Petty.