The California Workingman’s Party slate of candidates swept Berkeley’s first municipal election in 1878.

The party, led by the racist demagogue Denis Kearney, was the latest manifestation of California’s powerful Anti-Chinese Movement. In an Alameda County-wide election in 1879, 65 voters supported continued Chinese immigration, while 9,402 opposed.

In the midst of the economically depressed decade of the 1870s, many voters believed that the Chinese were occupying “white jobs.”

In Berkeley the main target of such criticism was R. P. Thomas’s Standard Soap Company, which employed many Chinese workers at its large West Berkeley factory. The company faced protests, demonstrations, a threatened economic boycott and even violence.

By 1886, R. P. Thomas said he no longer employed Chinese and hired only white workers. But that didn’t prevent Thomas from having a Chinese cook and houseboy at his Berkeley home.

Emulating San Francisco, Berkeley passed “sanitary ordinances” that made it difficult for Chinese laundries to operate. Some Berkeley Chinese residents regularly carried firearms to protect themselves against white violence. At least one Chinese man actually fired at a group of young white men who threatened to attack him. Even foreign Chinese students at the university faced discrimination both on and off campus. Clearly, Berkeley provided no refuge from the impact of California’s massive Anti-Chinese Movement.

Exclusion

During the 1850s and ’60s, the Anti-Chinese Movement was largely limited to California and a few other western states and territories. But by the 1880s, the movement had gone national, as evidenced by congressional passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. It banned almost all further Chinese immigration to the United States, and was the first significant immigration restriction law in American history. Ironically, it came just as the Statue of Liberty was being erected in New York harbor. However, the law did allow Chinese students to continue studying in the US, and that produced a small but steady stream of young Chinese nationals coming to Berkeley during the exclusion era.

The exclusion policy lasted for more than sixty years and produced a significant decline in the population of people of Chinese descent in California. Before 1882, most Chinese immigrants had been unattached young men, so there was a very small Chinese American second generation. By the 1890s, growing numbers of immigrants from Japan were taking the place of the now excluded Chinese. In Berkeley people of Japanese descent replaced Chinese as the city’s largest Asian group in the early twentieth century. They also replaced Chinese as the main target of both local and national anti-Asian activists. As a result, the Chinese exclusion policy was expanded to include Japan and the rest of Asia during the 1920s.

Finally, by the early twentieth century, many Berkeley neighborhoods were practicing a local form of exclusion by requiring property owners to include restrictive covenants in their deeds. These prohibited the sale or rental of the property to non-white people, thus excluding Chinese, as well as other persons of color. Not until 1948 did the US Supreme Court rule that enforcement of the covenants was unconstitutional.

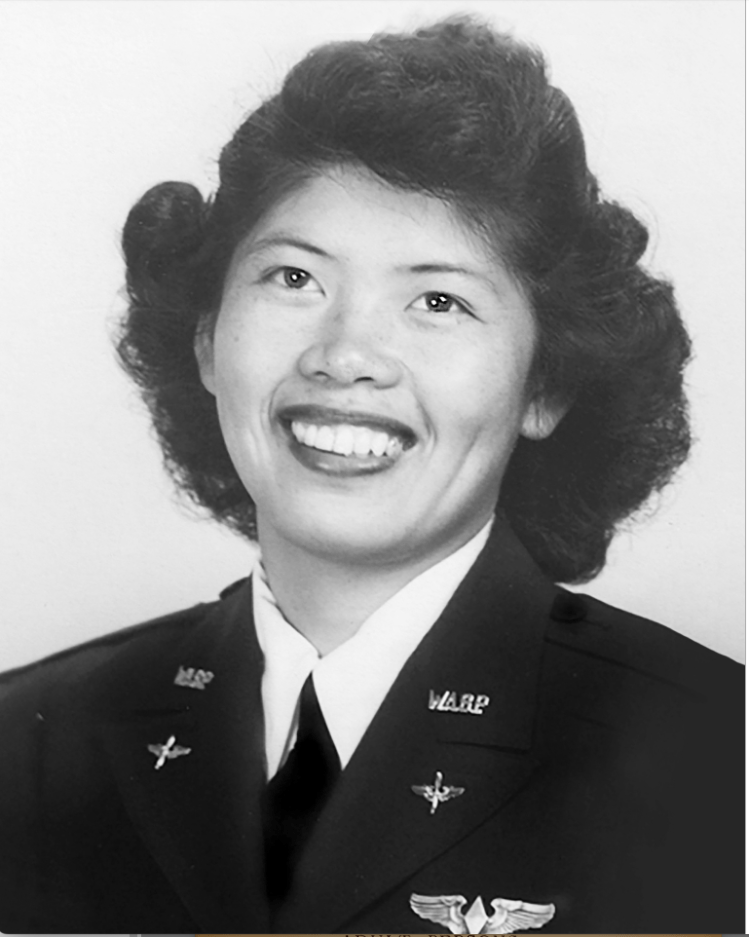

Maggie Gee and the Impact of World War II

Margaret “Maggie” Gee, a third generation Chinese American, grew up in Berkeley during the 1920s and 30s. After graduating from Berkeley High in 1941, she enrolled at Cal, majoring in physics. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, she left school to work at Mare Island Naval Shipyard as a draftsperson. Her mother also worked at the yard as a welder. The two Gee women were part of the huge workforce that made the Bay Area the world’s largest shipbuilding center during the war.

After some months, Maggie joined the WASPS (Women’s Air Force Pilot Service). While they couldn’t fly combat missions, the WASPS performed crucial functions, including testing new aircraft, ferrying planes from base to base, and even training male pilots. Although not initially recognized as part of the military, in 1977 Congress granted former WASPS veteran status and in 2009 awarded them Congressional Gold Medals. As one of only two Chinese American members of the group, Maggie received significant media attention both during and after the war.

Maggie Gee’s story is a case study of the major impact of World War II on Chinese American individuals and communities. China was a formal American ally, and in 1943, the government finally ended the exclusion era. For the first time in sixty years, at least small numbers of regular Chinese citizens could immigrate legally to the US. Also, the over-heated wartime economy created new economic and social opportunities. Anti-Asian racism and patterns of job and housing discrimination didn’t disappear, but people of Chinese descent had access to greater participation in mainstream American life and culture than ever before. While the armed forces segregated Black and Japanese American military personnel, Chinese Americans served in integrated regular units.

After the war, Maggie finished her degree at Cal and worked for many years as a research physicist at Lawrence Berkeley Lab. She also became a political activist, serving as a longtime member of the Alameda County Democratic Party Steering Committee, the state Democratic Party Executive Committee, and the Asian Pacific Democratic Caucus. After her death in 2013 at age 89, some prominent Asian Americans proposed that the Oakland International Airport be renamed after Alameda County’s most famous female Chinese American aviator, Maggie Gee.

The Tape Family

Before moving to Berkeley, Mary Tape accomplished one of the most important court victories on behalf of Chinese Americans during the Exclusion Era. A native of China, she arrived in San Francisco in 1868 at the age of eleven. Probably destined to work in a brothel, she instead found refuge in a home run by a group of white reformers called the Ladies Protective Relief Society. There, Mary learned English, converted to Christianity, and took the name of one of the staff members. In 1875 she married Joseph Tape, a fellow Chinese Christian and a young man who was already displaying a talent for business.

The Tapes tried hard to assimilate into mainstream American culture. They wore western clothes and lived outside of Chinatown. When their oldest child Mamie reached school age in 1884, Mary attempted to register her in the local neighborhood school. But Mamie was rejected, since San Francisco, like many other California communities, banned children of Chinese descent from the public education system. Mary sued, and in the case of Tape v. Hurley the state courts ruled that Mamie and other Chinese American children had a right to public education. However, much to Mary’s dismay, the judge allowed San Francisco and other California districts to establish segregated schools for Chinese students.

Berkeley, however, had so few children of Chinese descent that it was impractical to establish a separate Chinese school. The very few Chinese kids attended regular classes with white students. That may have been the reason why Mary and Joseph Tape moved their family to Berkeley in 1895, the year their youngest child Gertrude reached school age.

They bought a house at 2123 Russell Street. The family joined the Knox Presbyterian Church, located across the street from their new home. Joseph served on the local volunteer fire department and over the years bought and sold other Berkeley properties. Mary became a painter, an accomplished photographer, and a skilled telegraph operator.

After the elder Tapes died in the 1930s, various family members continued to live at 2123 Russell. Son Frank occupied the house in the 1940s, and after he died in1950, his wife Ruby lived there another twenty-five years. Only following her death in 1975 did the family finally sell the house. For the first time in eighty years, 2123 Russell was no longer a Tape family home.

- By Charles Wollenberg