Touching Ground

Chinese were living in the area that later became Berkeley as early as the late 1850s. By 1880, two years after Berkeley was incorporated, 55 Chinese were living in the city. After the 1906 earthquake and fire in San Francisco, many Chinese fled to the East Bay, resulting in the population of Chinese in Berkeley soaring to 356 in 1910 from the 97 who lived there in 1900.

Touching ground at UC

The University of California attracted Chinese to Berkeley. In 1895, the University established a Chair of Oriental Languages and filled it by hiring John Fryer, who mastered Cantonese and Mandarin while heading schools in China. In 1901, he developed a plan in which UC would take on “the role of educator of the gigantic empire…the tutor of China,” where the best Chinese would come and learn the skills necessary to manage a modern economy and government. Beginning with eight students in 1901, the program grew to 15 students the following year.

They speak English perfectly … are of a class that few Americans have seen. They have the quick intelligence of the ordinary American … the majority are Christian.

Berkeley Daily Gazette, 26 August 1901

Among the Chinese who later enrolled at UC was Fo Sun, a son of Sun Yat-sen, who graduated in 1916 with a B.A. from the College of Letters and Science.

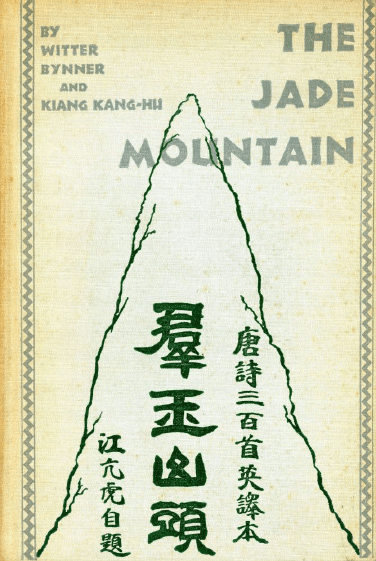

In addition to teaching students from China about modern economics, science, engineering and government, UC also provided education to non-Chinese about China’s history, culture, and languages. In 1914, UC hired Kiang Kang-hu to teach Mandarin Chinese and Chinese art and culture. Kiang also taught classes on Chinese civilization at the UC Extension facility in San Francisco. Before leaving UC in 1920, he donated to the UC library 10,000 books that had been in his family for generations. After leaving UC, Kiang collaborated with the American poet Witter Bynner on the book The Jade Mountain: A Chinese Anthology, Being Three Hundred Poems of the T’ang Dynasty, 618-906.

Chinese touched down on rocky ground

Chinese in Berkeley faced anti-Chinese attitudes

Even UC students from China, such as Tsung Yuen Chang, complained about the anti-Chinese attitudes in Berkeley:

We are treated like coolies, our stories of our eligibility to land discredited, and our certificates, showing we are students, regarded with suspicion.

With limited employment opportunities, Chinese were subjected to openly expressed hostility in the Berkeley Gazette, which demeaned them as “chinks,” “coolies,” and “celestials.”

Chinese in Berkeley faced anti-Chinese actions

The City of Berkeley passed two ordinances in 1905 that discriminated against the Chinese community. Using zoning as the justification, Ordinance 407 intended to interfere with the employment of Chinese by restricting where they could operate laundries.

Ordinance 421 attempted to eliminate places where Chinese relaxed and socialized, claiming they were places where Chinese engaged in illegal activity, such as gambling.

It shall be unlawful for a person within the limit of the town of Berkeley to visit … any … barred or barricaded house or room … where any cards, dice, dominoes, fan-tan table or any gambling implements whatsoever are exhibited or exposed to view when three or more persons are present.

These laws were vigorously enforced by Berkeley’s new police chief, August Vollmer.

Putting Down Roots

Living in a city with hostile anti-Chinese attitudes and actions, Chinese still put down roots in Berkeley as:

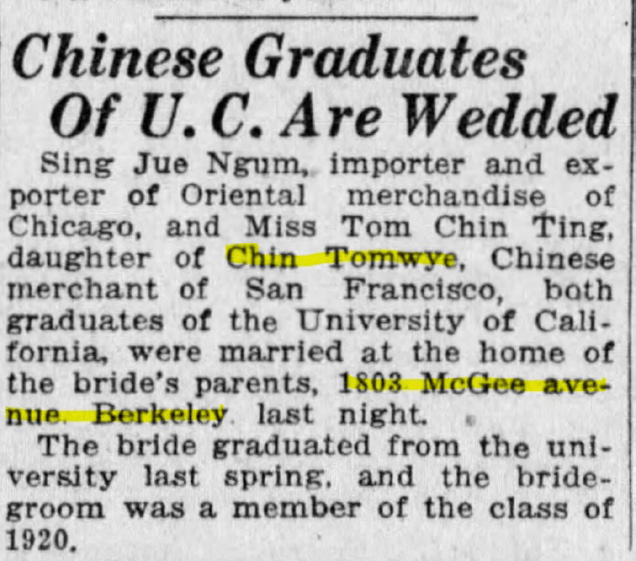

Homeowners: Chin Tomwye owned 1803 McGee by 1915.

Citizens: The percentage of the Chinese community in Berkeley who were American born, and thus citizens, increased from 8% in 1900 to 26% in 1910.

Oakland Tribune, 15 July 1921

Commercial property owners: Gee Guong Woo rented space in a building he owned on Dwight Way to the Hop Wo Bazaar, the Gee Thang wash house, and to non-Chinese businesses, such as the Steen grocery company.

Berkeley Daily Gazette, 30 Aug 1901

Chinese put down roots in Berkeley by establishing religious institutions

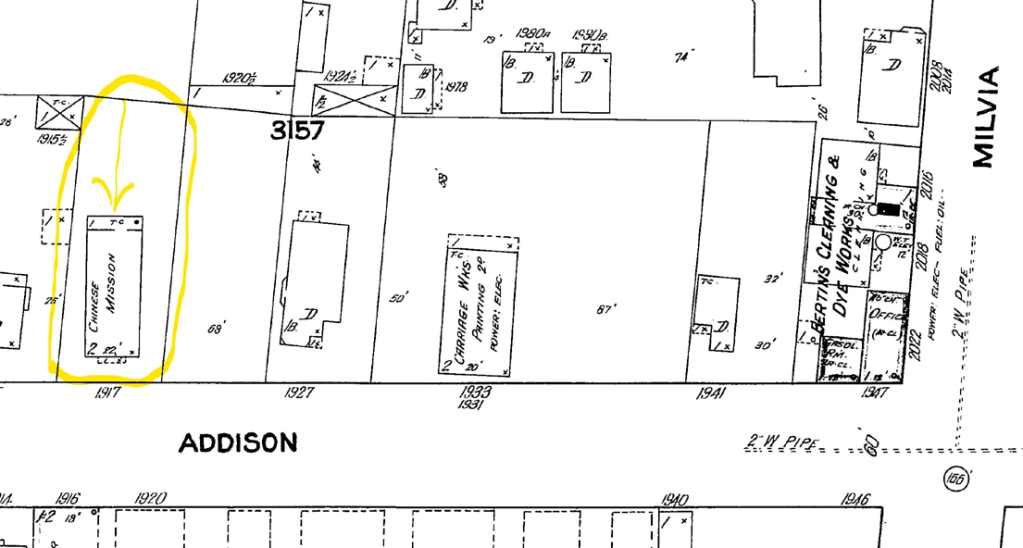

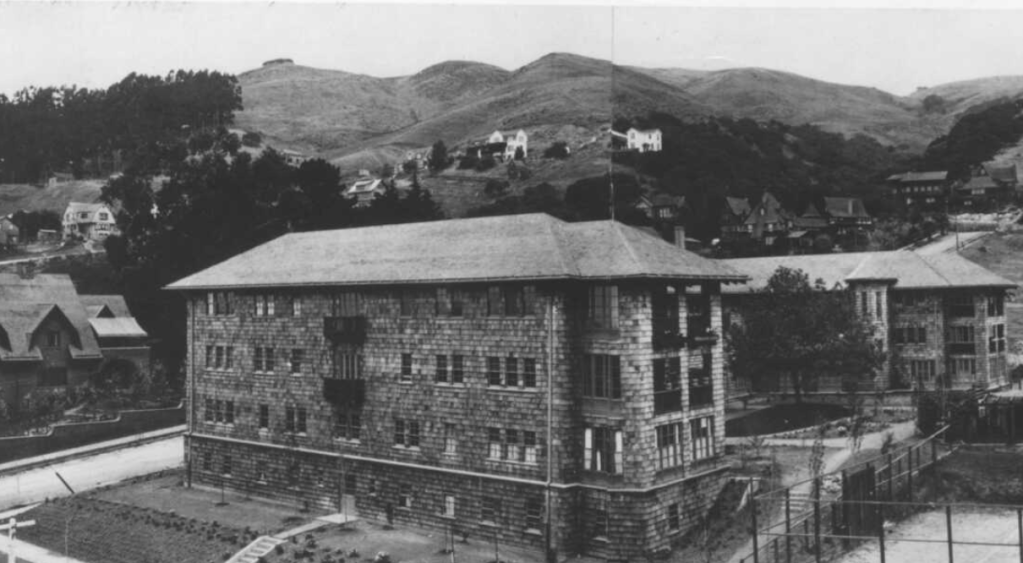

In 1900, a Chinese Mission Church was established at 1917 Addison Street, with living quarters and English classes for UC Berkeley Chinese students and Chinese classes for the children of Chinese immigrants. By 1920, it had become the Berkeley Chinese Community Church (BCCC) and the center of the city’s Chinese cultural and social life.

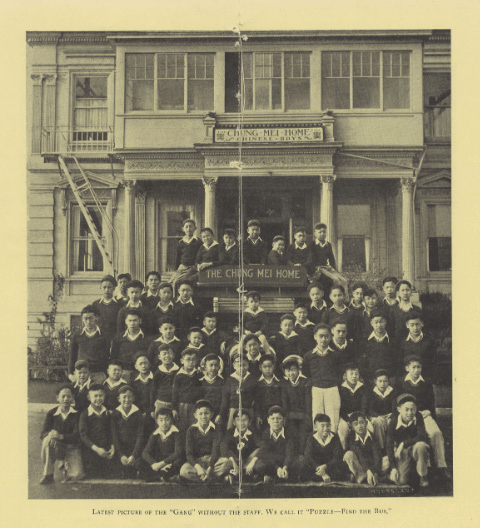

Congregational Mission, early 1900s

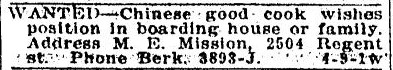

There was also a Chinese Methodist Episcopal Mission at 2504 Regent.

Chinese put down roots in Berkeley by establishing social welfare organizations

In 1923, the Berkeley Chinese Community Church collaborated with the American Baptist Home Mission Society and the San Francisco Bay Cities Baptist Union to establish the Chung Mei Home for Chinese boys at 3000 Ninth Street in Berkeley. The name marks the multicultural support of the organization, in which Chung means China and Mei means America. Opening with seven boys, it expanded within a few years to over 60 boys who had either been abandoned or orphaned. The institution later relocated to El Cerrito.

Chinese put down roots in Berkeley’s public schools

By 1906, 15 Chinese were attending Berkeley’s public schools; all were in grades four to six.

These students have adopted American modes of dress, and have become trained in American modes of living…I don’t believe the yellow danger is very apparent in this city.

S.D. Waterman, superintendent of Berkeley’s public schools

Chinese put down roots in Berkeley’s sports

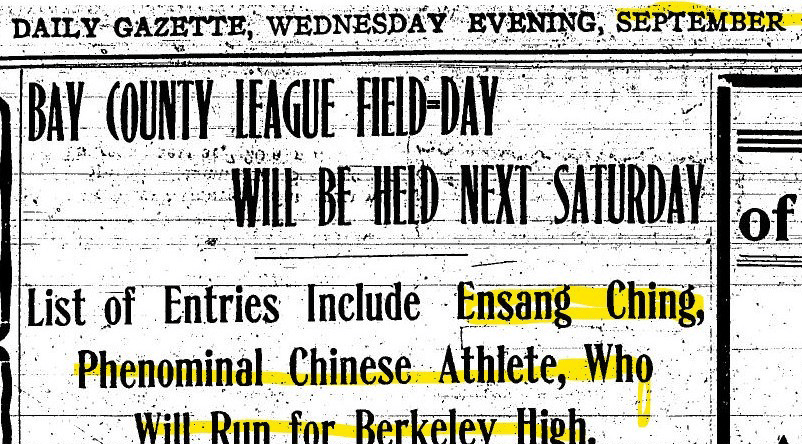

In 1901, Ensang Ching represented Berkeley High School in the 100-yard dash of the Bay County League.

By 1920, the basketball team at the Congregational Chinese Mission at 1917 Addison was one of ten teams that made up the area-wide Sunday School Athletic League. The team, managed by Wisdom Ding and with sharp shooter C. Chang at center, was undefeated and led the league. Chinese from the Congregational Chinese Mission also led Edison Intermediate School in 1920 to the intermediate schools championship.

Chinese put down roots by fitting into niches in Berkeley’s economy

Laundries

Hand laundries were a major source of employment for Chinese in early Berkeley. As early as 1880, Chinese had opened three laundries in the recently incorporated city. The 1908 City Directory for the East Bay lists five Chinese laundries in Berkeley.

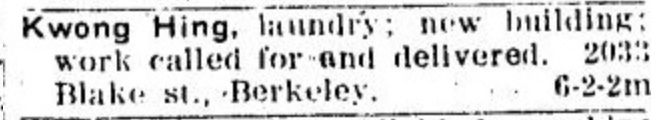

Over the years, Chinese opened other laundries, some advertising their services.

Chinese laundries, such as the Kwong Hing laundry, typically had drying platforms in the rear of the building. The Kwong Hing laundry, like other Chinese hand laundries, was self-contained as a place where the owner and workers lived and worked.

Factory Employment

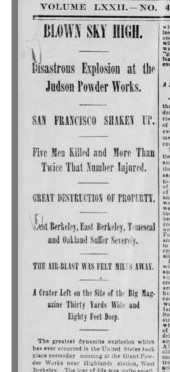

The Standard Soap Works, a major employer in Berkeley, fired the few Chinese it had hired and replaced them with whites during the 1880s as a result of anti-Chinese agitation. In contrast, by 1892, the majority of the Giant Powder Company’s 145 employees were Chinese. On July 9th, 1892, the Giant Powder Company, located at Fleming Point on the Albany-Berkeley city line, was the site of the largest dynamite explosion in the United States, killing at least four unnamed Chinese. After the explosion, the Giant Powder Company relocated to Pinole.

Chinese-owned factories

Berkeley Match Company

This factory, though a new one, has been successful. The entire labor force employed was Chinese, and about thirty were employed at the time of removal.

Berkeley Daily Gazette, 10 July 1902

The King Low Match Company

The 1910 census lists the names of the company’s Chinese workers, their place of birth, citizenship (six of the fourteen were born in California, and therefore citizens), and the variety of skills and duties they had.

Agriculture

As early as 1860, eleven Chinese immigrants were working as day laborers for $1.00 a day at the 24-acre Kelsey Ranch, which became part of Berkeley when the city was incorporated in 1878.

After 1900, Chinese continued working as farm laborers, but were also engaged in small-scale market gardening, raising fruits and vegetables. They sold their products at outdoor markets, peddled them door-to-door, and opened their own grocery stores to sell their produce.

Cooks, gardeners, and servants

Even before Berkeley was incorporated, Chinese were living in private homes as cooks, gardeners and servants. One of the earliest documented was Ah Jim, a 19-year-old living in the home of real estate developer Napoleon Bonaparte Byrne in 1870. By 1910, 25% of the 356 Chinese in Berkeley lived and worked in private homes. Their reputation as being good, steady workers in private homes resulted in businesses, clubs, UC fraternities and other organizations hiring them to perform similar jobs.

• Gee Shew and Gee Kim were employed as cooks and Wing Kee was employed as a laundryman at the Anna Head School for Girls:

• Luis Yen was employed as a waiter at the UC Faculty Club:

• Ghin Mee, Lee Tom, Gee Quong and Lee Maan were employed as cooks, Quong Hand was employed as a waiter, and Lim Yook was employed as a dishwasher at the Cloyne Court Hotel:

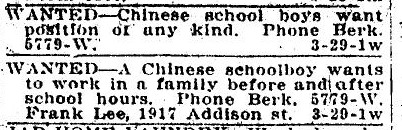

Frequent ads by Chinese, of all ages, seeking employment in private homes after 1910 indicate that being Chinese was becoming a positive asset in domestic work.

- Research and text by Michael Several