Homer Lee, founder of Lee’s Florist & Nursery

By Chilton Lee, 79, retired engineer at IBM and attorney in private practice

My father, Homer Lee, immigrated from China in 1926 at age 16 to seek a better life. His father was already in San Francisco and claimed that Homer was a citizen whose records were destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and arranged for his immigration as the son of a citizen. My father was detained at the Angel Island Immigration Center and initially was denied entry, but his father hired an attorney to appeal who was successful in getting that decision reversed.

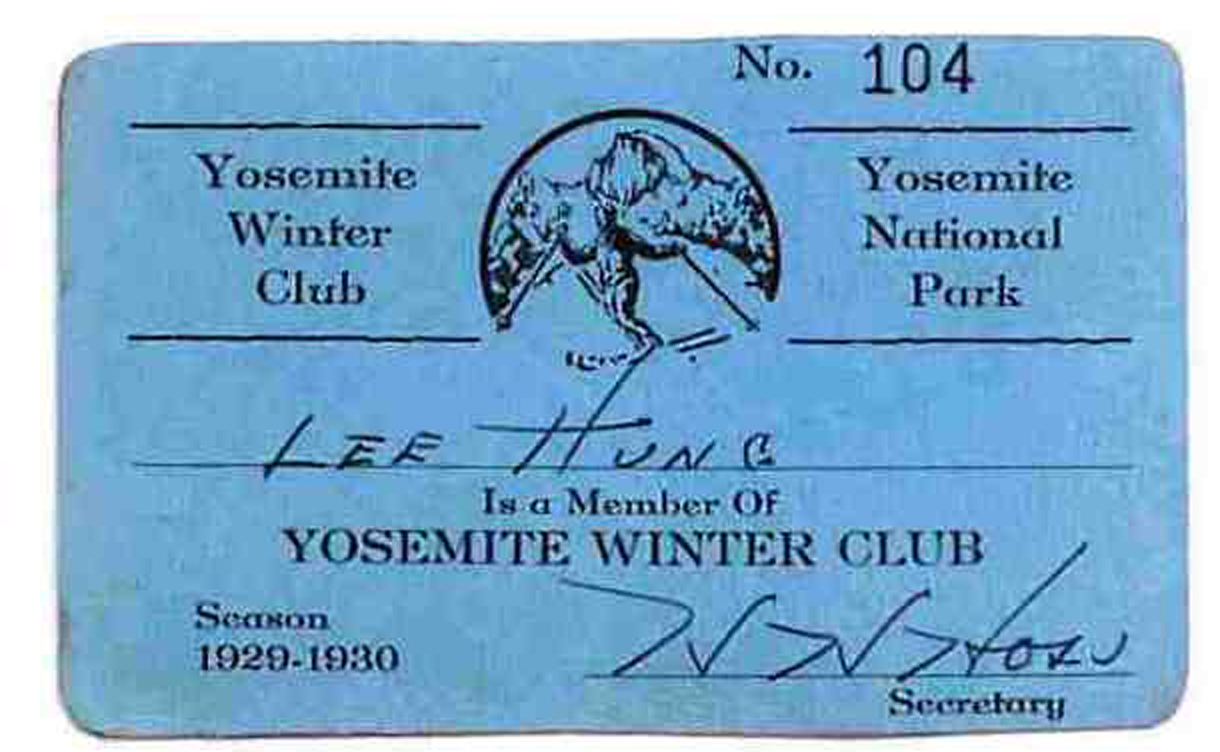

He lived in Alameda before moving to Berkeley and attended Berkeley public schools and graduated from Berkeley High in 1935. He worked as a houseboy for wealthy families in Berkeley. One of the persons he worked for was an executive at Standard Oil Company who was transferred to Yosemite National Park. My father moved to Yosemite with the family and worked in their household from 1929-31 and attended junior high school in Yosemite Valley.

He lived in Alameda before moving to Berkeley and attended Berkeley public schools and graduated from Berkeley High in 1935. He worked as a houseboy for wealthy families in Berkeley. One of the persons he worked for was an executive at Standard Oil Company who was transferred to Yosemite National Park. My father moved to Yosemite with the family and worked in their household from 1929-31 and attended junior high school in Yosemite Valley.

Homer Lee feeding a bear at Yosemite National Park, 1930

After moving back to Berkeley, he eventually lived in the dormitory above the Berkeley Chinese Community Church, where he met others who became lifelong friends. He also met my mother, whose family lived at 1919-1/2 Addison next to the church.

My mother’s father immigrated from China and her mother immigrated from Japan. They met while they were servants for wealthy families in Berkeley. Mother was born in Berkeley in 1908. Her parents were not citizens and were not allowed to purchase property in the US, so their four children bought a house at 2232 McKinley for them in the children’s names in the 1930s. My mother and her siblings and their mother were not sent to the relocation camps during the war, but my mother wore a badge that said she was Chinese. All four of the children went to Berkeley public schools and graduated from Cal. They all worked as civil servants because no one was hiring Asians.

By Wilton Lee, 75: continuing the family nursery

Before WWII, my father, Homer Lee, was a gardener, with his partner Albert Lew. They purchased supplies from San Pablo Florist & Nursery (San Pablo at Delaware), owned by the Nabeta family. When WWII broke out, the Nabetas had to leave everything to relocate to internment camps. My parents agreed to run their flower shop and nursery until they came back. Dad’s gardening partner, Albert Lew, took over Melrose Nursery (I believe owned by another Japanese family) on Russell Street in Berkeley. Albert operated the nursery until his retirement. The family closed the nursery and built apartments.

Mom and Dad successfully ran the nursery and kept in contact with the Nabeta family during WWII. Dad displayed a sign “Chinese American Florist” in the window of the flower shop (we still have that sign). After the war ended the Nabeta family came back and the business was returned to them.

Finding themselves without an income, my parents considered opening a laundry or restaurant, but the experience of operating a flower shop seemed the natural direction to follow. They had saved enough money to purchase a property on University Ave, borrowing money from family friends to build the flower shop (designed by Viggo Bertelsen) and nursery structures.

The office was originally our nursery and playroom, with a crib and bed, and also a small kitchen where Dad cooked lunch for us and his workers. In the back dad made a swing, and a sandbox in the greenhouse. As we got older, we were given chores around the shop and nursery.

Dad kept the shop (Lee’s Florist) open seven days a week and all the holidays, but found time after he closed to take us to Tilden Park, Lake Merritt, Indian Rock Park for family time. (Our mother passed away in 1952, when I was five and Chilton was nine). He would always close for a week in August to take us on a family vacation, usually to Yosemite (where he worked for two years), and other road trips …. Vancouver, Victoria, Portland, even to Disneyland the year after it opened!

I grew to like helping out at the shop and decided to pursue a degree in Horticulture from Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo. Dad had a new interest in property management, buying, fixing, and renting properties out, and I began to take more responsibilities at the shop.

In 1970, Homer retired and turned over the reins of Lee’s Florist to me, but he still found time for his first love of growing and propagating plants. Most of the plants he worked with were native to China.

Homer Lee

After taking over, I expanded to a second location in the Elmwood, and also took over the oldest flower shop in Berkeley, the Berkeley Florist, from Steve Porras. Later I consolidated the shops into our University Avenue location. Six years ago, I turned over the reins of Lee’s Florist & Nursery to the third generation, my son Jared. He has made it through the Covid years and has plans to continue the tradition that his grandfather and grandmother started in 1946, providing flowers for all occasions at reasonable prices.

Lee/Chan family: Chinatown commerce and 100 years in Berkeley

By Aimee Baldwin, fifth generation Chinese Californian, artist

The first in my family to arrive in California was my great-great-grandfather, Chan Kay Choy, in the 1850s, the founder of the Chinese community in Napa. He arranged Chinese laborers for farmers, and owned a store, Lai Hing, in the segregated section of Napa, where he sold food and dried goods to the laborers. My great-grandmother Chan May Choy was born in Napa in 1886, and raised in an old-fashioned way, without attending school, spending her time on domestic chores.

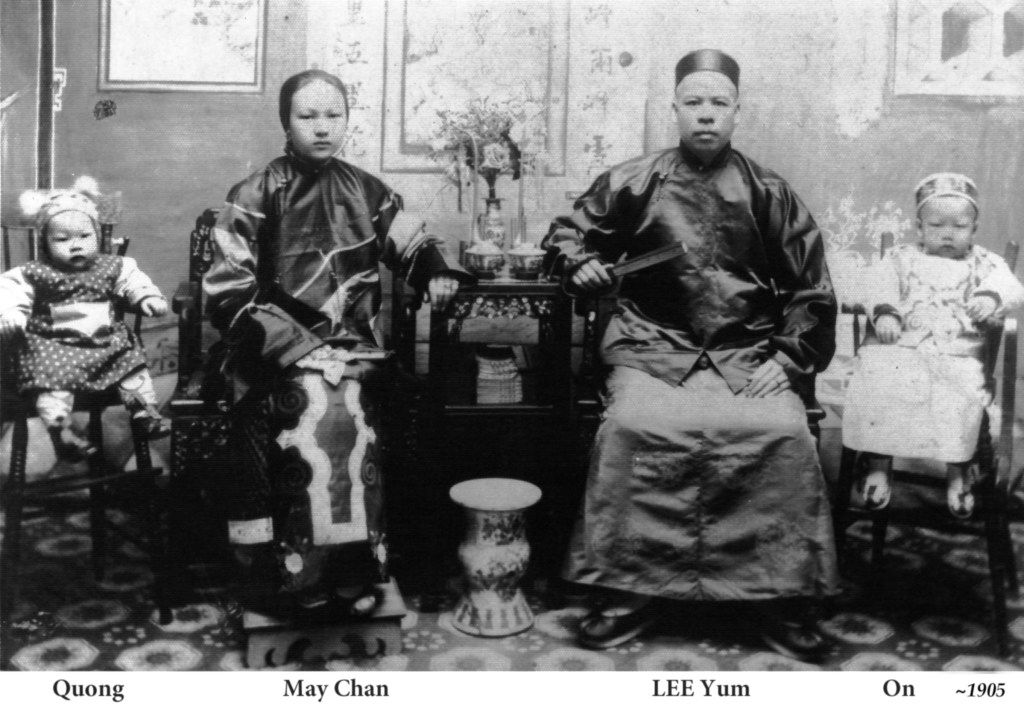

In 1901, May Choy married Lee Yum, a prosperous businessman 25 years her senior. Lee Yum had arrived in San Francisco in 1881, sent from China by his family with the hope that he could send money back to his village. He had an arranged marriage before he left China, to reinforce permanent ties to the village. He returned to China twice in the 1880s, each visit resulting in a son. Eventually, he earned enough money to support his first wife and two sons who lived in China, but they never came to California.

Lee Yum’s early jobs in San Francisco were in a shoe factory, cigar factory, and a wool mill. In order to save money, he ate one meal a day and lived in extremely crowded bunk rooms. Lee Yum was very entrepreneurial and started a lucrative business as a property manager, through a white friend who was willing to have his name used to rent property in San Francisco, Oakland and Stockton. Lee Yum divided and subleased units to a variety of Chinese businesses: restaurants, grocery, herb or dry good stores, and most profitably as gambling halls.

After the fire and earthquake of 1906, May Choy and Lee Yum lived in Oakland briefly but then returned to San Francisco, and Lee Yum helped three of his brothers get to America. They started a seafood business of harvesting clams, all done with difficult manual labor. The whole family pitched in long hours, and slowly updated the business model to remain successful through changing times, eventually ending up as a wholesale business of selling bay shrimps in Oakland Chinatown through the 1940s.

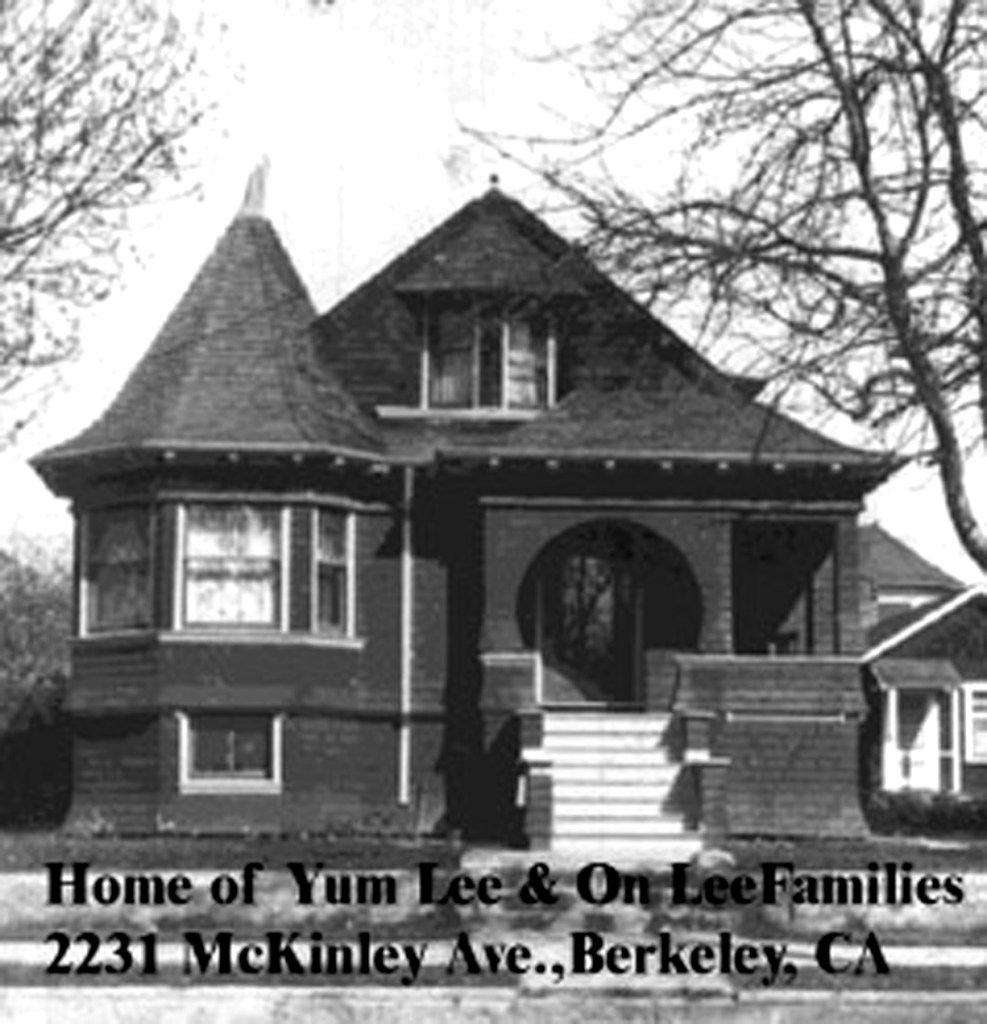

When Lee Yum had sons born in the US, he used their names to buy properties in San Francisco and Berkeley. The family moved to Berkeley in 1923 in hopes the sons would attend the University of California. I don’t know if it was traditional sexism or lack of resources, but they did not plan for their daughters to attend college, and my grandmother resented it.

When my family was in the process of buying the house on McKinley Ave, and becoming the first Chinese on that block, white neighbors began a petition to prohibit us from moving into the neighborhood. However, a white woman who lived on that block had spent time living in China with her missionary family, and spoke up on behalf of my family, saying that Chinese people should be allowed to move in.

The family had thirteen children, nine of whom lived to adulthood. Those who grew up in Berkeley of the right age attended Berkeley public schools. May Chan and Lee Yum both passed away by 1928, leaving a difficult home situation, as the oldest brother dropped out of UC Berkeley so he could raise the younger siblings with his wife.

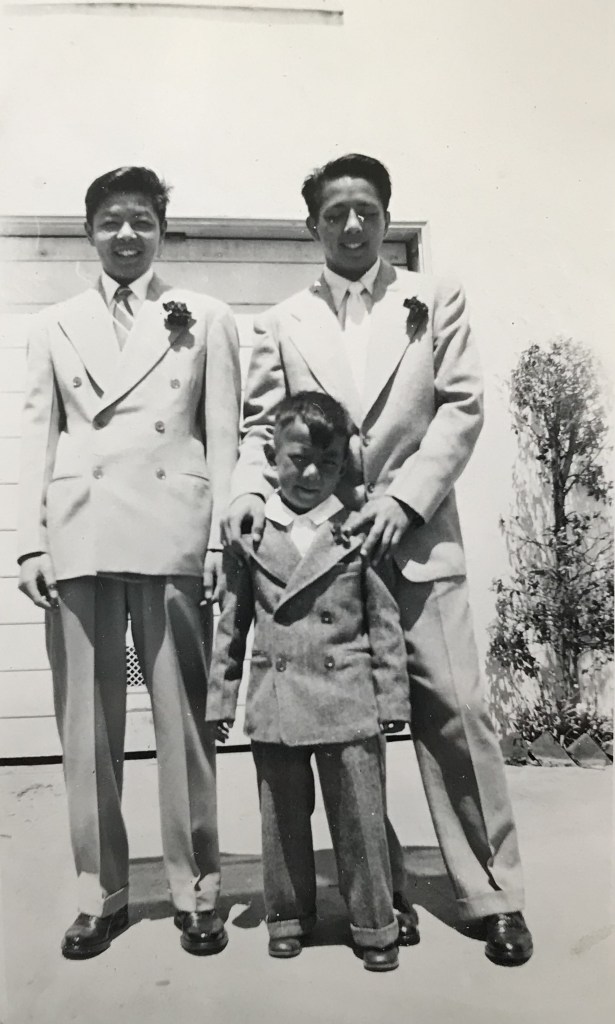

On the steps of McKinley house, 1938. L to R: Linnie, Chong, and Yuen (Roger Yuen Lee)

My family was very close with the small, tight-knit Chinese community and the Berkeley Chinese Community Church. This generation of my family growing up in the 1920s felt the need to “act American,” not speaking Chinese, assimilating into western culture, and making an effort to avoid the stigma of foreigners which their parents’ generations faced.

My grandmother and several of her siblings, including Roger Yuen Lee the architect, raised their families in Berkeley, so my mother and many of her generation also attended Berkeley public schools. Lee Yum’s sons who graduated from UC Berkeley between the 1930s and 1950s became middle-class professionals, and subsequent generations of our family went to college. Roger Yuen Lee raised his family in a house he designed on the 2100 block of McGee Ave, until he was able to move to Kensington, again to a house he designed. More members moved out to El Cerrito or other suburbs further away to live “the American dream.” I am the youngest in the family to be raised in Berkeley and attend Berkeley public schools (Berkeley High class of 1993), and one of the two family descendants still living in Berkeley.

Kee family: Nevada’s Wild West

By Aimee Baldwin, fifth generation Chinese Californian, artist

My great-grandmother, Ah Cum, was born in 1876 in Carson City, Nevada. Through some contacts, her parents promised her hand in marriage, when she came of age, to a labor contractor named Ah Chung Kee.

After a violent anti-Chinese riot in Carson City, her parents moved back to China with their other children, leaving Ah Cum to be raised by family friends until she was old enough to be married.

Ah Chung Kee (born in Kaiping, China) had immigrated to San Francisco in 1864. Because he could read and write English, he served as a labor contractor for the Virginia and Truckee Railroad (1869-1872) in Nevada and became friends with Duane L. Bliss and Henry M. Yerington, railroad, mine, and logging company owners.

Chung Kee and Ah Cum married around 1891, and settled in Hawthorne, NV where they ran a farm, small merchandising store, and restaurant. They developed an amicable relationship with the nearby Paiute Indians, serving the Paiute in the backyard of the restaurant (due to segregation; most restaurant patrons were single white men working as miners). The Kee family also exchanged their knowledge of farming techniques with the Paiute, in exchange for fishing rights in nearby Walker Lake (Paiute had exclusive fishing rights there).

When Chung Kee died in 1909, Ah Cum took over the farm and restaurant, and raised their six children. In the 1910 census, she was the only woman listed as a farmer in the state of Nevada. The family moved to other small towns in Western Nevada, as required for economic survival, eventually moving to Oakland, CA.

My grandfather Frank Kee, the youngest son of Ah Cum, had assorted unskilled labor jobs around the Oakland area, such as cook, or as a driver taking people from Chinatown to the gambling halls of Emeryville. He married Jackie Lee (of Lee/Chan family in Berkeley).

In the 1950s, my grandfather Frank and his brother William opened one of the few non-white-owned casinos in Las Vegas (other casinos only allowed white patrons and kept Black or Asian employees out of sight). Their success earned the resentment of certain elements of the population, and a series of “mysterious” fires destroyed not only their casino but also an African American-owned casino that had been built recently, thus ending potentially successful minority-owned casinos in Las Vegas for a while. William died of a heart attack as a result of his efforts to put out the fire. Unable to continue the business on his own, my grandfather sold the casino.

Growing up in Berkeley in the 1950s, my mother recalled facing racism while shopping at the Hinks department store: she said she had to wait until every single white person in the store got served before she could get any staff to help her at the counter.

She told me that at Berkeley HIgh and UC Berkeley, she wasn’t allowed to join social groups or sororities––except those which were specifically for Asians. Even though she had many friends, and they were not necessarily Chinese, she still had experiences which made her feel like an outsider, or excluded.

My uncle attended Boy Scout activities of the Berkeley Chinese Community Church, but never “felt especially Chinese” growing up. He grew up during Berkeley’s peak activism and hippie years in the 1960s and 70s. He says he had only one brief foray into activism when he was in college, attending student protests in San Francisco advocating for Asian American and Ethnic Studies; however, the hippie influence has endured in his life.

Despite the “Americanization” of my grandmother’s generation, or my mom marrying a Caucasian (with much disapproval from my grandmother), my mother made an effort to connect my brother and me to our Chinese heritage. Being the first of our family to be able to openly choose a home location in Berkeley without racial restrictions, my mom chose to buy a house next to Monterey Market, where my brother and I could attend the Chinese Bicultural program at Jefferson (now Ruth Acty) Elementary School. She later co-founded the Hip Wah Chinese summer program, and spent many years after that fighting for more inclusion and representation of Chinese and Asians in Berkeley schools.

I have pretty much always “passed” for being white––most disturbingly, when people mistook my mother for being the nanny. It is difficult to not be recognized as multiracial, but not as bad as hearing people downplay the amount of racism that Chinese people have faced. The stereotype of Asians now as the model minority, and experiences of recent immigrants, has replaced the memories of earlier discriminatory stereotypes, prejudices, and injustices. Most people know little of this history, except for the Chinese Exclusion Act. Almost nobody talks about the 19th century hate crimes like lynchings, or burning down of Chinatowns. Two generations of my family faced overtly and explicitly racist housing discrimination within Berkeley.

When I was growing up, I had so many cousins, family friends, or classmates who were mixed that I thought it was the norm to be mixed race until I was at least nine years old. I have never identified as Chinese as much as culturally Californian. My Chinese identity is tied up in experiences specific to early California Chinese immigration, experiences that are not shared with later Chinese immigrants, whose cultural connections are different. I feel that most people who grow up in California live some type of multicultural experience as I do.

Louie Family

By Lorraine Louie, Born in Hong Kong, raised in Berkeley, BA University of California, Berkeley, MA Columbia. Worked as consultant, coordinator, director at non-profits

My father, F.S. Louie, came from China to the US in 1913 to join his father––who had come to Nevada earlier as a sojourner. My father earned a graduate degree in Chemical Engineering from Columbia University, where he met my mother, Wai Sue Chun, a 1929 Columbia graduate. Seeking better employment, my parents returned to China in the 1930s. Despite moving from one province to another during WWII to escape the Japanese bombing, my parents were able to create business opportunities wherever they went.

In Guilin, my father established an enamelware factory; the factory was bombed and the family moved to Hong Kong, where I was born. While my father went to the US for machinery to rebuild the factory, my mother managed an import business in Hong Kong by herself. We five children stayed home with nannies.

When civil war broke out in China, my father sent for us. With the sponsorship of a senator from Oregon, we were able to immigrate to the US in 1949. Berkeley was chosen because my parents hoped we children would attend UC Berkeley in the future. My parents used savings, investments, and a loan from my mother’s brother to buy two houses, one to live in and one in the industrial area of Berkeley for business.

While I was growing up, my parents worked seven days a week in their business importing and distributing Chinese-designed bowls, cups and plates to Chinese restaurants across the country. (See more on that at On Food and Ceramics)

The two of them were a working pair, rarely at home, often traveling. We did not have nannies in the US. I remember that my mother would send me postcards from exciting places, and she would leave cash in a box on the table, to pay for the takeout food from local Chinese restaurants. Luckily in Berkeley there were many!

Unlike some other Chinese American children of my generation, I was spared a sense of shame for being Chinese because I had my three older siblings as role models. They were almost adults and were filled with the optimism and striving of young people, discovering new vistas and possibilities. In China, they had witnessed so much suffering; here, they were determined to leave that suffering behind, and they were very disciplined. More importantly, however, they were secure in their identity as Chinese. They knew the beauty and sophistication of their own culture.

By the time I was eight, my three older siblings had grown up and moved away. I too left Berkeley, only to return as a married mother of two babies. I chose to be a stay-at-home mom because I did not want my children to be latchkey kids as I had been, with no adults at home. However, I did want my children to be raised in Berkeley, a town of which I am fond, and where people are much more open-minded. As an expression of our family’s connection to Berkeley, some of us have created UC Berkeley Alumni scholarships, which we hope will make a contribution to Berkeley’s future.

“My father was the first Asian to buy in that neighborhood”

By Robert Chung, born in Berkeley in 1953; teaches at UC Berkeley

By Robert Chung, born in Berkeley in 1953; teaches at UC Berkeley

My father, James Chung, was born in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1922, one of fourteen children. His parents had been born in China, but claimed that their birth certificates had burned in 1906. My father’s father worked in a shop in Chinatown. He and my mother went to Commerce High School near City Hall. He served in the Army Air Force in WWII. On the G.I. Bill, he got a degree in accounting at Golden Gate University and bought a house in Berkeley at Chestnut near Delaware in 1948.

My mother, Virginia Louie, arrived in S.F. via Angel Island at the age of six. She stayed overnight at Angel Island. Later, when my school was going on a field trip to Angel Island, she told me she had spent enough time there and never wanted to see it again. She and her mother came from Guangdong and were joining her father, who worked as a laborer in S.F.’s Chinatown.

My parents spoke Cantonese at home, but my father died when I was four years old. My mother spoke Cantonese with her family and friends. My grandmother never spoke English. We spent the Chinese holidays with her––New Years and the Moon Festival. The Christian holidays––Christmas and Easter––we celebrated with my father’s relatives.

I was born in 1953, the youngest of four. There were a lot of Finns in the neighborhood when my parents moved in. My father was the first Asian to buy in that neighborhood. Japanese and Chinese followed. Gradually, the Finns moved out. When I was in kindergarten at Franklin, there was a mixture––Asian, Black, Caucasians and Hispanics. But even before the beginning of Berkeley schools integration in 1967, Asians started moving out––to El Cerrito or to the hills.

Being Chinese was not a big part of growing up in Berkeley for me. Because there were so many stereotypes, I denied that I was Asian. Now there is greater awareness of Chinese culture in Berkeley. Before, we were trying to demonstrate that we were as American as possible. I quit Chinese school as soon as I could. How stupid was I? I studied Latin and Spanish. At the time, I thought the way to minimize conflict was to become as American as possible. I wanted to strip away all external appearance of being Chinese.

I tell my kids they are multicultural: Chinese, French, Jewish, Italian. But when people look at them, they are Asian….but yes, it is different now, being Asian. My kids are pretty comfortable in their own skins.

Wong Yun-Cham

By Art Wong, born in Berkeley, UC Berkeley BA 1963. Retired emergency medicine physician,“Because it offered care to everyone regardless of background or economic status”

By Art Wong, born in Berkeley, UC Berkeley BA 1963. Retired emergency medicine physician,“Because it offered care to everyone regardless of background or economic status”

My father, Wong Yun-Cham, immigrated from China to Los Angeles in the 1920s to learn to be a car mechanic, which was a new skill in those days. However, under pressure from an acquaintance from his Chinese village, he was talked into taking over the running of a grocery store in Nogales, Arizona. He went back to China, returned with a wife and started a family. They had five children in Nogales: Lily, Jack, Rose, Bill and Florence.

Eventually, my father wanted his family to return to China because he felt it was losing its Chinese culture. However, on the way back, Japan invaded China, so they decided to stay on in the Bay Area. They chose Berkeley because they hoped their children would attend UC Berkeley. Using the children’s names, my parents purchased land at Chaucer and San Pablo, where Father built a grocery store with apartments above and a duplex on the back of the lot. Then I was born, and my father passed away shortly after.

I never felt discriminated against anywhere as a kid, or never perceived it…maybe I was oblivious. I was kind of a free range kid—my mother was not so strict with me, being the last of six kids. I remember at [Burbank] Junior High School we would take our bikes with some pals, “the three musketeers”: They would come over and pick me up, and after school we would play basketball: a Black guy, and a Japanese, and myself. We still have a strong group of friends to this day, from junior high and high school. We were so integrated; a true melting pot, in a way that other cities were not at that time.

My older siblings spent many extra hours running the store and supporting the family after finishing their professional jobs in the day. My mother held onto the family store until I finished college, then she sold it.

Between the early 1950s and the mid 1960s, perceptions of Chinese changed significantly. People wouldn’t hire Chinese in the early 1950s. People asked my older sister’s husband why he bothered to study to get his CPA license, since nobody would hire a Chinese person for that. But by the time I went through college, fifteen years later, things had changed.

My brothers said engineering was boring and recommended I study medicine, so I did. I became interested in emergency care because it offered care to everyone regardless of background or economic status. In the 1990s, in reaction to the possibility that the elimination of affirmative action college admissions would diminish opportunities for underrepresented or disadvantaged minorities, I started a scholarship program through the UC Alumni Association to assist children of immigrants or first in families of color to attend college. My proudest achievement in board work was creating the UC Alumni scholarship, and the proudest recognition I ever got was getting elected as the first, and only, Chinese American trustee of George Washington University.

Berkeley Chinese Community Church, United Church of Christ

Established in 1900, 2117 Acton Street, Berkeley

During an era of racial discrimination, the Berkeley Chinese Community Church acted as the social and cultural center for Chinese in Berkeley for the first half of the 20th century. It was a place where Chinese, whether American citizens or immigrants, could have help settling down and finding acceptance safely within an established community in Berkeley.

It was founded in 1900 as a Chinese Mission school and by 1906 had its own building at 1917 Addison Street. In 1914 it became an independent congregation. The Mission was dedicated to serve the needs of students from China studying at UC Berkeley, and to teach English to Chinese immigrants. Upstairs from the Church, it offered boarding rooms for rent, one of the limited options available for individual Chinese to find rental housing in Berkeley.

Besides Sunday services, it had a Christian education program, Chinese literature club, basketball club, social clubs, youth groups including Boy Scouts, and hosted dances, banquets, and cultural activities. It conducted after-school Chinese language study classes, simultaneously creating a connection to Chinese roots and daycare services for working parents.

In the 1950s, when the BCCC was in need of a new location, Homer Lee turned over a purchase contract to the Church for a large piece of land where he had intended to build family housing. Roger Yuen Lee, whose family had close ties to the church since the 1920s, designed the new church at 2117 Acton Street.

In the later 20th century, as limitations from discrimination for living in Berkeley diminished, the BCCC still offered connections to the Chinese community and Chinese culture. In the 1970s, Ester Lee, the wife of a BCCC minister, established the Chinese Bicultural program in the Berkeley Public Schools. In the 1980s, the BCCC was the original site for the children’s Chinese summer program, Hip Wah. The church still offers services and Bible study in Chinese and English.