Bodega Bay: Returning to Harbor Foliage in the Eastern hills has turned yellow Passing gulls act as our guides Smoke rises from the evening cooking Will she be watching for me from the window?

Excerpts from interviews

Liao Ling-te

(Came from Taiwan in 1969. Artist, calligrapher, poet and potter)

“A Kind of Meditation”

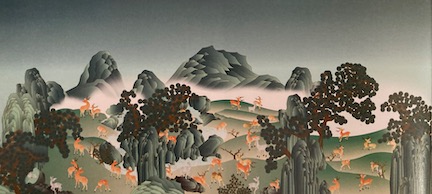

Hunting Scene

A poem by Wang Wei (699-759) Translation and calligraphy by Liao Ling-te

Sounds of hunting horn and bow string pierce the howling wind It’s the general’s party hunting by Wei City Their falcons’ eyes sharp in the withered grasslands The snow has gone, swift steeds lightly stride A quick drink in Xin Feng city, then back to barracks Looking back to where the hawk was downed The evening mists over the plains lie boundless

How did I learn my calligraphy? Actually, it was my hobby when I was young. I was encouraged by my teachers and won prizes. When I went to college to study Chinese literature, I was a teaching assistant in the calligraphy class. I learned by copying the old masters’ calligraphy, which is the traditional way. It became a daily routine when I came to the United States, as a kind of meditation.

How did I learn my calligraphy? Actually, it was my hobby when I was young. I was encouraged by my teachers and won prizes. When I went to college to study Chinese literature, I was a teaching assistant in the calligraphy class. I learned by copying the old masters’ calligraphy, which is the traditional way. It became a daily routine when I came to the United States, as a kind of meditation.

In 1969 I came from Taiwan to the University of Minnesota for the graduate program in East Asian Studies. But, for a better chance in the job market, I switched to studying computer programming. It landed me a job at UC Berkeley, where I stayed for twenty-five years. But my main interest has always been art and literature.

While I was at the University of Minnesota, I had the opportunity to study pottery in the Ceramics department. In China, pottery is one of the major arts. My calligraphy and painting were a natural addition as a way to decorate my pottery. Hand-made pottery adds joy to daily life.

Most Chinese immigrants in the United States have a science or tech background, so it is difficult to find others who share my interests among my social circle. Fortunately, I have joined local groups that do plein-air painting. My painting fuses both Eastern and Western aesthetics, which gives me a chance to share my art with others.

Lin I-Kuan

(came from Taiwan in 1965 to be a graduate student and stayed)

“I never thought of going back to Taiwan to live”

I came to Berkeley in the fall of 1965 because my second older brother was studying for a PhD in mathematics at Cal, which made it easier for us because we, my third brother and I, were going to work to make some money before going to graduate school. We lived with our second brother and his wife. In Berkeley, I worked at an Irish restaurant called Brennan’s on University Avenue west of San Pablo. I worked as a busboy and peeling potatoes sometimes. I remember they had very good roast beef. The cooks were Cantonese immigrants from China, maybe second generation, and they were very friendly.

I came to Berkeley in the fall of 1965 because my second older brother was studying for a PhD in mathematics at Cal, which made it easier for us because we, my third brother and I, were going to work to make some money before going to graduate school. We lived with our second brother and his wife. In Berkeley, I worked at an Irish restaurant called Brennan’s on University Avenue west of San Pablo. I worked as a busboy and peeling potatoes sometimes. I remember they had very good roast beef. The cooks were Cantonese immigrants from China, maybe second generation, and they were very friendly.

The following summer we went to San Jose to work in the canneries––that was very interesting, but tiring! You had to work quickly and continuously because you had to put a whole tall rack of fruits onto the conveyor belt which kept moving. It was not that bad because we were young. I remember at night we fell asleep really fast!

How did I feel here? My brother was studying at Cal and there were quite a few students from Taiwan, and he had a circle of friends, so I felt comfortable. Since I just came from Taipei, I noticed that the city of Berkeley was very different. I was very impressed by how orderly, clean and not so crowded it was. The street signs, street lights, etc. were very different from what I had been used to in Taiwan.

In the fall of 1966, I enrolled in the Statistics Department of Oregon State University and got a master’s degree in 1968. Then, I came to Cal to study for my PhD in industrial engineering and operations research, but after two semesters, I wasn’t interested anymore and started working at the University’s President’s Office in University Hall. I worked there from 1969 to 1978.

In Berkeley, we raised two children, a daughter and a son. They speak some Mandarin, but more Taiwanese. They cook Chinese dishes, but not everyday like my wife .… We celebrate Chinese New Year together––our daughter and her family just live in Marin. The children’s families are pretty Americanized.

Yes, from the first when I was thinking about coming to America, I was going to stay. But this is interesting––Taiwan’s economy began to develop rapidly in the ‘70s and ‘80s. My college classmates who stayed in Taiwan all had very busy careers––and even have successful businesses. But I never thought of going back to Taiwan to live and work there. My parents wanted me to go back, but I like this country, a lot. Just like any country, there are always some problems, but this country, because of its Constitution and political system, eventually can deal with the problems peacefully. There is some violence sometimes, but mainly peacefully. For instance, when I worked at the President’s Office, the anti-Vietnam War protests were getting really strong, but it wasn’t really violent.

Liu Cheng

(founder of Eureka Therapeutics)

“Then I had this Eureka moment!”

In the ‘80s, every Chinese student wanted to come to the US for higher education. It wasn’t a question of whether, it was when. There weren’t many Chinese students [when I came to UC Berkeley in 1990]. I still remember the number: it was 154. Today it’s probably in the thousands.

In the ‘80s, every Chinese student wanted to come to the US for higher education. It wasn’t a question of whether, it was when. There weren’t many Chinese students [when I came to UC Berkeley in 1990]. I still remember the number: it was 154. Today it’s probably in the thousands.

My advisor, professor Giovanna Ames, told me, “Cheng, I am not only your professor, I am also your mentor,” and she gave me all these books to read. I read the Little House on the Prairie books and then The Iliad and The Odyssey––that’s where the name of my company, Eureka Therapeutics, comes from. I remember a big debate in China: China was very developed technologically, but it didn’t have modern science––why? With the Greeks, you study because you want to know the truth. Back then, I was always trying to find some practical use for my science—to develop a technology or a drug. At the time going to a company was a dirty word. My parents….

I went to Chiron, which was started by UCB professor Ed Penhoet. While Dr. Penhoet was running Chiron as the CEO, he was still teaching biochemistry at Berkeley, but he only took $1 a year for his teaching. I thought: “You can be a great scientist, but also develop drugs and help people.”

I had been thinking about developing a cancer drug from the very beginning. It started when I was a kid. Because my parents were medical researchers and doctors, we lived next to the hospital. So, as kids, we saw suffering every day. The cancer patients––that look in their eyes, it was just burned into my memory. So when I heard that Chiron was developing cancer drugs …. I worked for Chiron for nine years. Then in 2006, it was bought by Novartis for $10 billion. I thought, “This is the time to make a change.” I started my own company. It was crazy. I didn’t even have a project. I just had a dream––I wanted to cure cancer…. After the financial crisis, 2008, we didn’t have investment money. We survived by making reference antibodies and providing technical services.

In 2010, Dr. David Scheinberg from Memorial Sloan Kettering called and invited me to explore a crazy idea: finding a proxy on the cell’s surface of the tumor-specific target inside the cancer cell. In 2012, while visiting David in New York, Scheinberg introduced me to Dr. Renier Brentjen. Renier was working on T-cell therapy, arming a T-cell with an antibody to treat cancer…. On the flight back, I had a Eureka moment: “What if you have the antibodies for the tumor specific intracellular targets on the one hand, and the power of the T-cells on the other, that might be the solution!”

I looked this morning: in 2022, you had about 800,000 new cases of liver cancer in the world and more than half are from China. If this liver cancer drug can work, the technology can be applied to many other cancers. In fact, we just signed a partnership with the US National Cancer Institute to go after another cancer, pancreatic cancer.

Lin Jiang

Reflections upon listening to the Berkeley Chinese Music Ensemble

Listening tonight I think: there is hope…. On the one hand, Chinese have always been the model immigrants. And that’s not so hard, to make it academically and financially. On the other hand, I understand those Chinese who decide to go back at a certain point. If you stay here, you are missing something.

Listening tonight I think: there is hope…. On the one hand, Chinese have always been the model immigrants. And that’s not so hard, to make it academically and financially. On the other hand, I understand those Chinese who decide to go back at a certain point. If you stay here, you are missing something.

Tonight, hearing traditional Chinese tunes woven into contemporary music––music played on the Chinese zither, erhu and pipa as well as on Western instruments––memories from the past are resuscitated. It is very meaningful, these ancient Chinese tunes written and played by contemporary Chinese musicians. I feel there is hope: there will be new art here that reflects our culture, but is appreciated by all.

Marilyn Kwock

Growing up Chinese in Berkeley in the 1960s

Growing up in Berkeley was a tug of war between the Chinese family culture of my parents vs. the very big, loud, and dynamic mix that was Berkeley in the 1960s. My classmates were diverse economically, racially, and socially, many of whom I knew by name from junior high through high school. They brought Black Power, counterculture, world politics, and other issues to campus while I watched and listened from the periphery. During the People’s Park protests, I watched the National Guard in Provo Park from my biology class window––then we were sent straight home under martial law. I saw the action on TV like most of the nation.

Growing up in Berkeley was a tug of war between the Chinese family culture of my parents vs. the very big, loud, and dynamic mix that was Berkeley in the 1960s. My classmates were diverse economically, racially, and socially, many of whom I knew by name from junior high through high school. They brought Black Power, counterculture, world politics, and other issues to campus while I watched and listened from the periphery. During the People’s Park protests, I watched the National Guard in Provo Park from my biology class window––then we were sent straight home under martial law. I saw the action on TV like most of the nation.

What I experienced during these formative years was a hugely broadening education. I developed a great tolerance of the diversity in people, as well as a degree of irreverence, for which I am very grateful. However, I did not join in the protests of the day; it was safer not to make waves or bring attention to myself. I attended Cantonese school at the Chinese church briefly, but resisted as everyone around me spoke English. There was always a tension, with my Chinese-ness having few outlets outside of my family for many years.