Five Generation Families

The Tominaga Family

Chio Tominaga was not literate in Japanese or English, but she was fluent in sewing, cooking, and song. She plucked her stringed samisen, sang traditional Shigin, and on New Year’s Eve, prepared all the special foods that her husband Yotaro and eight children would test taste before guests arrived the next day. Even as a senior citizen, Chio would prepare Oshogatsu dishes and start the New Year with a tumbler full of sake poured from a large bottle, recalls Judy Tominaga Fujimoto, a granddaughter.

Chio was born in 1883 in Kumamoto Prefecture, Kyushu. At age 29, she boarded the Tenyo Maru to San Francisco to marry Yotaro Tominaga, 39, a contract laborer whom she had never met although they came from the same village. She arrived at Angel Island on September 19, 1912, and married Yotaro two weeks later.

Yotaro was born in 1873, the youngest of four sons. At age 23, in 1896, he traveled to Hawai’i on a three-year labor contract. In 1905, he moved to San Francisco. Friends would often present his photograph as their own to potential picture brides, according to the family. Chio and he were a hardworking couple, farming rice, fruit, and almonds in Sutter, Butte, Sacramento, and Santa Clara counties. They had six boys and two girls.

The family settled permanently in Berkeley in 1937. As “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” they circumvented the 1913 Alien Land Law that prohibited Japanese from buying property by purchasing a house at 1623 Tyler Street, a red-lined area, in the name of their second son Joe, a U.S. citizen by birth. Yotaro and Chio joined the Berkeley Higashi Honganji Temple. Their older sons started a landscape gardening business, and the youngest two enrolled in Berkeley schools.

In 1942, with the World War II concentration camps looming, the family rented the Tyler Street house and sought refuge in Elk Grove in the Sacramento Delta area, which they hoped would be exempt from forced removal. But when all of California became an exclusion zone, the Tominagas were sent to the Fresno Assembly Center. Yotaro died at the county hospital from lack of proper treatment for diabetes.

Chio and the children were sent to the prison camp at Topaz, Utah. Four sons served in the U.S. military during and after the war: Melvin (442nd Regimental Combat Team), Sam (232nd Engineers), Tom (Military Intelligence Service), and Henry (U.S. Army in Occupied Germany).

After the war, Chio returned to the Tyler Street home. With the passage of the 1952 McCarran-Walters Act, she studied for the U.S. citizenship test and became a naturalized citizen in 1955. In 1960, the Tyler Street house was sold, and Chio moved to a small house on Sacramento Street, where she gardened, cooked, crafted, and sewed, until she suffered a stroke in 1979. Her children then moved Chio to a senior convalescent home, where she celebrated her 100th birthday in 1983. Chio lived to be 103 years old.

Through five generations, the Tominaga family have been a vital part of Berkeley life. Five of Yotaro and Chio’s children (Nisei) owned homes and raised their families in Berkeley. Six of their grandchildren (Sansei) graduated from UC Berkeley. Granddaughter Judy, daughter of Melvin, married Bill Fujimoto, and together from 1978 to 2009 they managed the Fujimoto family business, Monterey Market. Bill and Judy’s daughter, Amy Fujimoto Chen, served as co-director from 2019 to 2024 of Daruma no Gakko, a legacy summer program that teaches Japanese American history and culture. Chio and Yotaro’s descendants include thirteen grandchildren (Sansei), twenty-one great grandchildren (Yonsei), and twenty-nine great-great grandchildren (Gosei), who live not only in California but in Illinois, Florida, Washington, Hawai’i, and Japan. And eight descendants still live in Berkeley.

When Chio died, her prolific production of quilts that were not claimed by family found their way to garage sales and flea markets. One collector, Eli Leon, admired Chio’s work and left his sizable collection of her textiles in a bequest to the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive. Curators are now examining the roots of Chio’s distinctive creations and hope to mount an exhibition of them. Chio’s work still sings.

The Fujii Family

Kurasaburo and Kikuyo, c. 1917, with fourth child Haruko. Courtesy Fujii family.

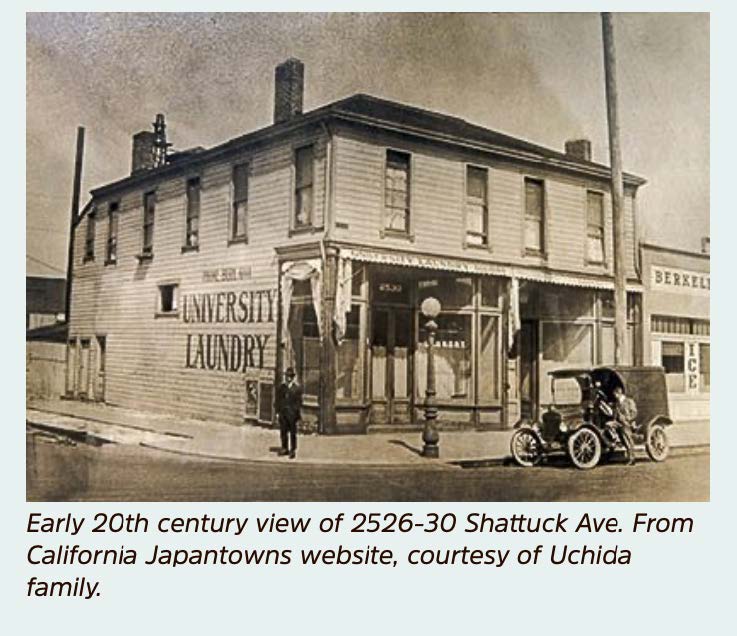

In 1914, Kurasaburo Fujii’s entrepreneurial spirit led him to form a five-family laundry cooperative on Shattuck Avenue and Blake Street with the Imamuras, Kinbaras, Tsubamotos and Tokunagas. They started the work day at 4:30 a.m. at the University Laundry, ate breakfast at 6 a.m. and delivered orders by horse and buggy. Scalding hot water was recycled into a communal bath that a dozen friends and family members enjoyed together after work.

Kurasaburo was born in Fukuoka Prefecture in Kyushu in 1881 and arrived in the U.S. in 1903. He was working at a nursery in San Francisco when the 1906 earthquake drove him and many Japanese immigrants across the bay to Berkeley. Kikuyo Naganuma was born in 1891 near Kurasaburo’s village. She was promised to him in marriage at age 12 and lived with his family until she traveled to the U.S. in 1909 to marry him. They had seven children. The fifth, Michiko, was born at the laundry in 1922, but grew up in a two-story house on 2903 Harper Street because the family was able to purchase the home in the name of their doctor, Dr. Hajime Uyeyama, a Berkeley-born U.S. citizen. At the time, approximately 500 people of Japanese descent lived in Berkeley.

The University Laundry at 2526-30 Shattuck Ave. opened in 1914, enduring anti-Asian racism. An Oakland Tribune article said that Chinese and Japanese laundries were a “source of infection” and that “it is no uncommon occurrence to see Japanese laundry wagons working all day Sunday.” (Jan. 11, 1911, p. 104.)

Michiko graduated Berkeley High School and entered Cal, but her education was interrupted in 1942 by President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Uncertain about the future, Michiko and her boyfriend, Ki Uchida, decided to marry. They were holding a small ceremony at the Harper Street home when a stranger knocked on the door and photographed them. Years later, Michiko and Ki learned that Dorothea Lange, the famous photographer who documented the WWII incarceration for the War Relocation Authority, was the mysterious stranger with a camera. Michiko and Ki saw their wedding photos for the first time at the National Archives, after the war.

From left: Oyone Uchida (Ki’s mother), Akira Hayashida (Michiko’s brother-in-law), Haru Fujii Hayashida (Michiko’s sister), Michiko, Ki and Warren Eijima (Ki’s best man). Photo: Dorothea Lange, April 27, 1942. National Archives.

Their honeymoon had taken place in a horse stall at the Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno that had been converted into a detention site for 8,000 Bay Area American Japanese. Months later, the Fujii family, having lost three decades of investment in the laundry, was transferred to the Topaz, Utah, concentration camp. Michiko and Ki had two daughters born at Topaz. Their second, Leslie, grew up in Berkeley after the war. She married another Berkeley native, Gary Tsukamoto, whose younger brother, Ron, was born at the Tule Lake camp in northeast California. After the war, the Tsukamotos returned to Berkeley and Ron became the first Japanese American officer hired by the Berkeley Police Department, in 1969.

Officer Ronald Tsugio Tsukamoto.

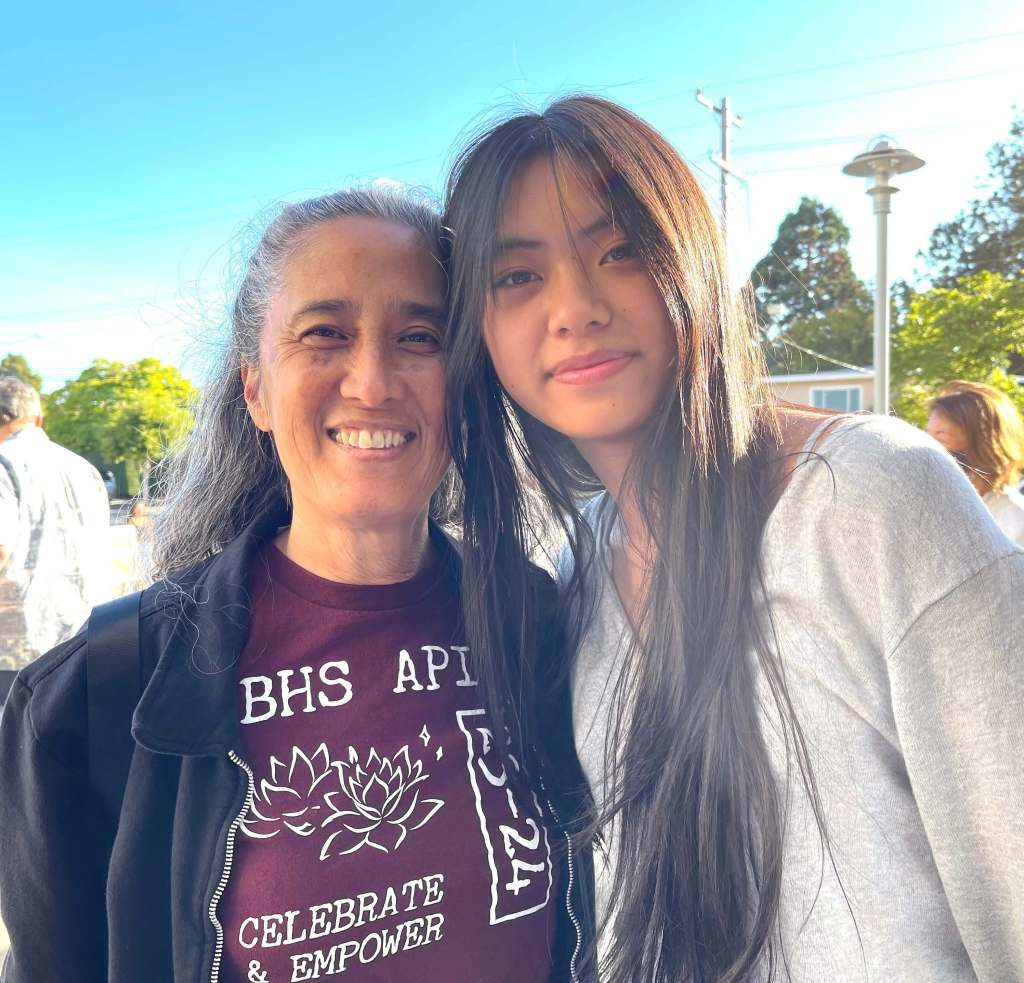

Tragically, nine months later, he was shot to death at age 25 while talking with a motorist he had stopped. In 2000, the city named the new fire and police headquarters the “Ronald T. Tsukamoto Public Safety Building,” a memorial to a killing that was never solved. The Northern California Asian Peace Officers Association holds a dinner every year in which they present a scholarship in Ronald’s name to someone who is pursuing a degree in criminal justice or law enforcement. Leslie works to improve women’s education. She has served on the board of the Japanese American Women’s Alumnae Association of U.C. Berkeley since 2010. Her sister, Joyce, also born at Topaz, in 1944, still lives in Berkeley. One of Joyce’s daughters, Dana, taught Ethnic Studies and Japanese American history at Berkeley High School for 30 years. Joyce’s granddaughter, Marianne Mah, 17, is co-president of the Berkeley High School Asian Pacific Islander Club and traveled to Japan with the Sakai City-Berkeley friendship delegation in 2024. She is the fifth generation of the Fujii family.

Above: Kurasaburo and Kikuyo with the first seven of 16 grandchildren, c.1949. Their family ultimately grew to include 19 great-grandchildren and 26 great-great grandchildren. Below left, Dana Tom (fourth generation Fujii) ), retired Berkeley High School teacher of Ethnic studies, with Marianne Mah, (fifth generation Fujii) BHS student and activist in Asian American Pacific Islander issues. Below right, Ron and Gary Tsukamoto, c. 1946. Courtesy Fujii family.

John Fujii, the sixth child of the immigrant family, wrote that his parents returned to the Harper Street home in 1945 and that Kurasaburo found work as a church custodian. At holiday dinners, he said grace in Japanese, wearing a white starched shirt, Leslie remembers. He died at home at age 78 in 1959. Kikuyo died at age 90 in 1982. In 2017, the University Laundry building was designated a City of Berkeley Landmark by a unanimous vote of the City Council. Supporting testimony was given by Leslie, the Berkeley JACL and Kaz Oyamada Iwahashi, who testified to the surprise of those in attendance that she, too, had been born at the laundry, in 1929. Her father had worked there as a clerk, according to her birth certificate, she said.