Japanese American activism didn’t begin with the sixties.

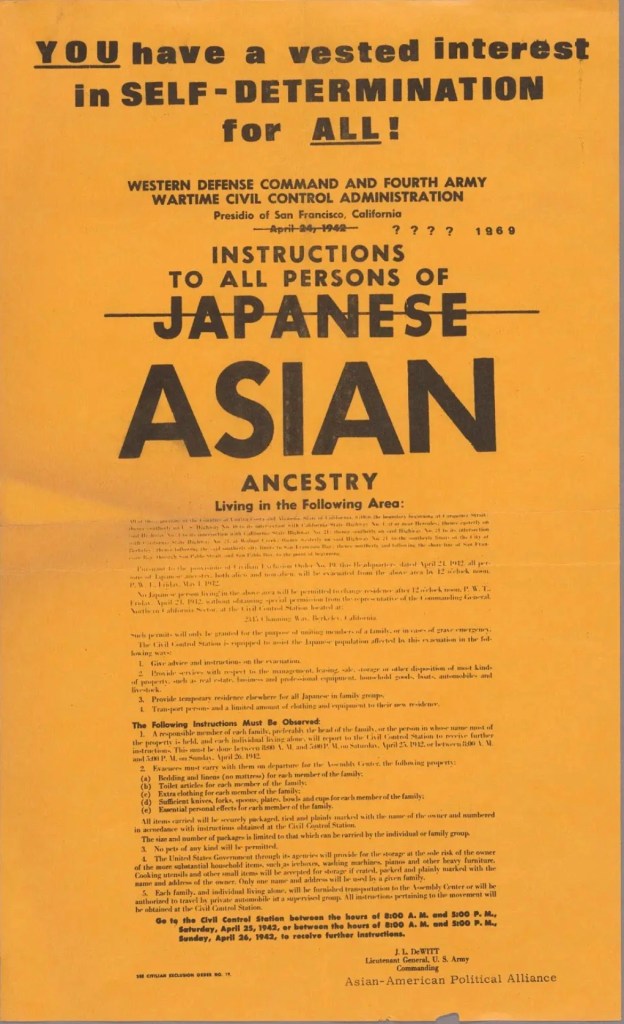

From the time Issei immigrants arrived in Berkeley, they were subject to exclusionary attitudes and laws that prevented naturalization, land purchase and social integration. Issei found ways to evade the 1913 Alien Land Law by purchasing property in the names of their children or other U.S. citizens. Takao Ozawa’s case to fight for naturalization went to the Supreme Court in 1922. Decades later, the push for ethnic studies in the 1960s, the Third World Liberation Front movement at U.C. Berkeley and anti-war activism paved the way for a pan-Asian American identity. The term “Asian American” was born in Berkeley.

1909

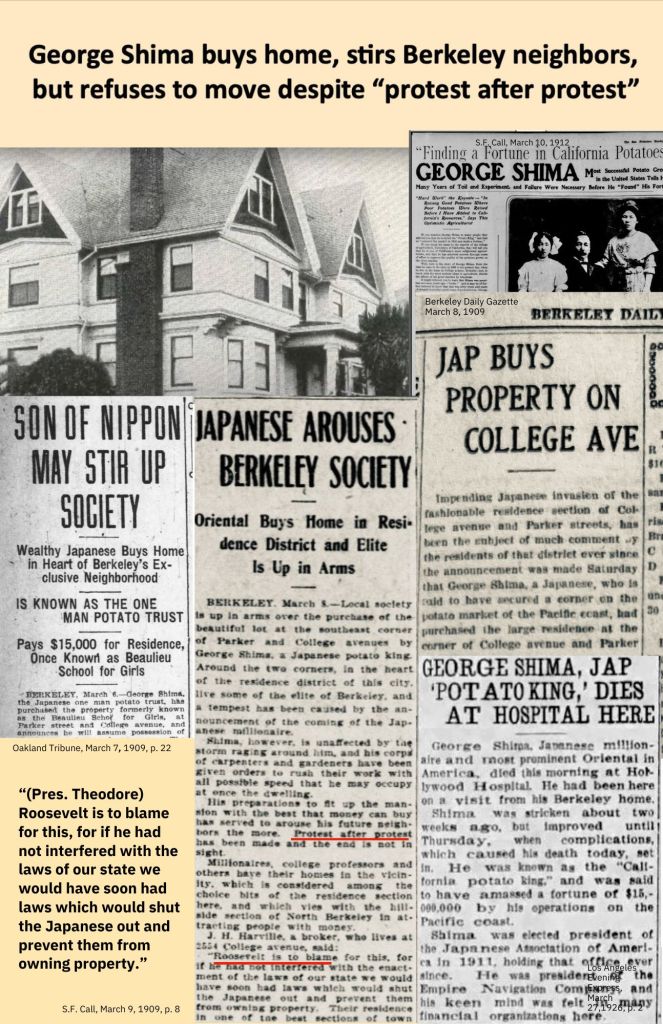

George Shima (1864-1926), known as “the potato king,” was born Ushijima Kinji in

Kurume, Kyushu, and arrived in the U.S. in 1889; his first job was as a domestic. He later made millions in the Sacramento valley in potato crops. In 1909, he bought an estate on College Avenue despite opposition. As head of the Japanese Association of America, he pushed for naturalization rights through the courts.

1922

Takao Ozawa, a Berkeley High School graduate and a student at U.C. Berkeley, fought for naturalization rights in the historic Ozawa vs. United States case. In 1922, the Supreme Court ruled against his argument that he was “white” and assimilated. This landmark Supreme Court case denied eligibility for citizenship to Japanese immigrants.

It was not until the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 that

Asians were allowed to naturalize. Under the Nationality Acts of 1790 and 1870, the federal law had restricted the right of naturalization to aliens who were either “free white” or of “African nativity and descent.” The ambiguity of the former category led Ozawa to challenge racial categories.

Ozawa was born in Kanagawa, Japan, on June 15, 1875, and immigrated to San Francisco in 1894. He graduated from Berkeley High School and attended the University of California at Berkeley for three years until 1906, when he moved to Honolulu. He was fluent in English, practiced Christianity, and worked for an American company. He was married to a Japanese woman who was educated in the U.S. In his legal brief, he argued that his skin was as white as or whiter than the average Caucasian’s, but more importantly, he cited his character. “In name Benedict Arnold was an American, but at heart he was a traitor. In name I am not an American, but at heart I am a true American.” The Supreme Court ruled on November 13, 1922. Justice George Sutherland, who was an immigrant from England, presided over the case and upheld the lower court ruling and declared Ozawa racially “ineligible for citizenship.”

The Supreme Court ruled on November 13, 1922. Justice George Sutherland, who was an immigrant from England, presided over the case and upheld the lower court ruling and declared Ozawa racially “ineligible for citizenship.”

Resistance to Incarceration

During the war, Japanese Americans, including those from the Bay Area, protested mass incarceration without due process in a variety of ways. One of the most well-known legal cases was that of Fred Korematsu, who lived in Oakland. Korematsu refused to be removed, and attempted to change his appearance to avoid arrest. After his eventual arrest, he became the subject of a test case which challenged the constitutionality of Japanese American incarceration. He was found guilty of avoiding military orders, but his case set the groundwork for the movement for redress decades later.

Many Japanese Americans also resisted conditions in camp and demanded changes in lodging, medical treatment, and sanitary conditions. Hajime Uyeyama, a beloved Berkeley doctor, was punished for his advocacy around improving medical conditions in camp. As a result, he and his family were sent from Tanforan to Tule Lake, and later transferred to Amache.

The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) was active in the immediate years after the war in an effort to receive compensation from the government for property and earnings lost as a result of the incarceration. This led to the 1948 Evacuation Claims Act, which provided some compensation to a small percentage of those incarcerated. The JACL also advocated to pass the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act giving Issei the right to US citizenship, and allowing them to own land for the first time.

Artists and writers, including Berkeley’s Chiura Obata, Miné Okubo, and Yoshiko Uchida, documented life behind bars. Their art reached large audiences and helped to garner support for the redress movement after the war.

1960s

A community mix of activist university faculty, students and Berkeley residents brewed a rich history of Asian American activism that planted seeds for the future. Among the many political leaders, including scholars, were Paul Takagi, Raymond Okamura, Yuji Ichioka, Ronald Takaki, Wendy Yoshimura and Patrick Hayashi.

The birth of the Asian American Movement began in 1968 in Berkeley when student activists Emma Gee and Yuji Ichioka coined the term “Asian American” to replace labels with colonial connotations such as “Oriental.” They called their new student organization Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) to unite

people of different Asian descent groups for common goals. The Alliance was integral to the Third World Liberation Front protests which demanded that

more faculty of color be hired and curriculum broadened to include the experiences of Black Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and Asian Americans.

Gee and Ichioka’s home at 2005 Hearst Avenue in Berkeley is recognized as the birthplace of the Asian American Movement and is a historic landmark.

During two Third World Liberation Front strikes at San Francisco State and U.C. Berkeley in 1968, for the first time students from all Asian ethnic groups came together with other communities of color and demanded the right to determine for themselves how their stories would be told. The program promoted activism.

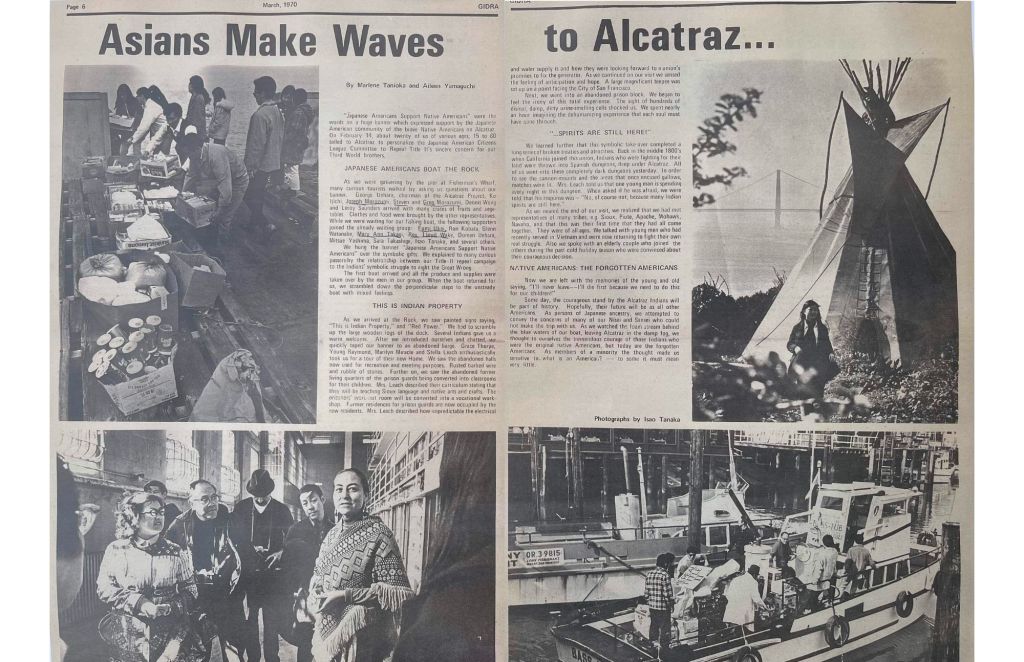

Japanese American activists also joined the fight for Native American rights, particularly during the occupation of Alcatraz in 1969-1970.

“I was very fortunate that my parents were very outspoken about [incarceration], and also very much outspoken about what was going on in our country, because by the time I was in high school, this was the sixties, there was the rise of Martin Luther King Jr., and the recognition for the need for voter rights in the South. I’m very grateful that my parents actively involved me in that. And later on my mother set forth a great example by participating in the way that she could with the occupation by the Native Americans on Alcatraz in the early seventies. She went around every Monday morning to all of the Catholic churches to get their left over votive candles, because they had no electricity in Alcatraz… and took them to the Berkeley pier, where a boat would show up for supplies.”

-Arlene Makita-Acuña was a curator of Roots, Removal, and Resistance.

1980s

Attorneys Dale Minami and Don Tamaki, both graduates of Berkeley Law at the University of California, led a team that successfully challenged in 1983 the convictions of Gordon Hirabayashi, Minoru Yasui and Fred Korematsu, who had challenged the government’s curfew and exclusion orders aimed at Japanese Americans. The U.S. Supreme Court had upheld their convictions and the curfew and exclusion laws in 1943 and 1944. Their convictions were overturned 40 years later, based on government misconduct that involved lying about the alleged disloyalty and acts of espionage committed by Japanese Americans in order to justify the urgent need for exclusion.

The Berkeley-born writer, Yoshiko Uchida, may not have described herself as an activist, but her books for youth readers about the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans have served to resist the erasure of history and erosion of memory. Her books on incarceration, particularly Desert Exile, helped to educate the general public about incarceration during the fight for redress.

Poet, memoirist and playwright Hiroshi Kashiwagi was a “No-No Boy” at Tule Lake concentration camp, meaning that he refused to swear his loyalty to the United States during incarceration. “No-no boys” were treated with suspicion by the government and were often transferred to higher-security camps such as Tule Lake.

Kashiwagi was invited to the White House in 2011, where he met President Obama and the First Lady Michelle Obama. Kashiwagi and Sadako Nimura Kashiwagi met at U.C. Berkeley when both were students. Hiroshi died in 2019 at age 96. Sadako lives in Berkeley.

2000 – Present

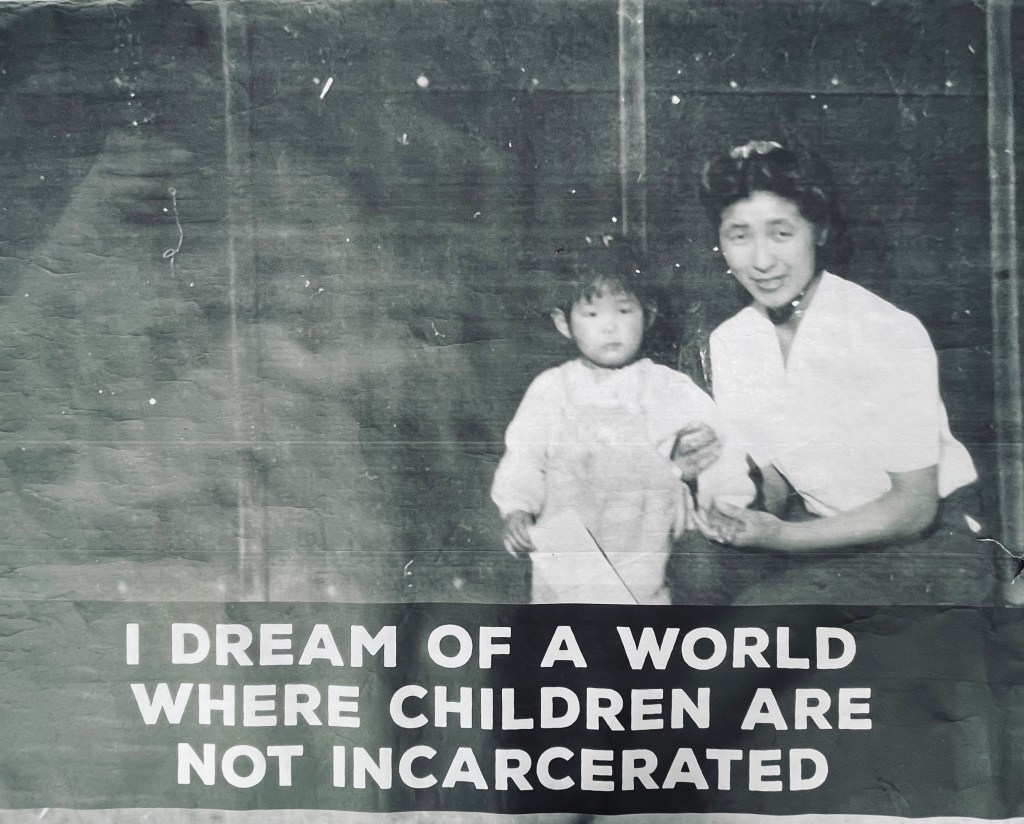

Satsuki Ina (pictured as child, above, and at left) attended U.C. Berkeley 1962–1966, during the Free Speech Movement. She was told by her parents not to get involved, a legacy of the trauma they experienced as dissenters to the WWII incarceration. Ina later became a psychotherapist specializing in trauma, and in 2019 co-founded the Tsuru for Solidarity national movement to shut down migrant detention camps. This large poster is a reproduction of one used at a Tsuru for Solidarity protest in front of Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where a government facility to house unaccompanied migrant children was planned until two protests cancelled it. The poster shows Satsuki (age 2 years) with her mother, Shizuko, in 1946 at the Tule Lake concentration camp. Satsuki wrote about her parents’ wartime dissent in The Poet and the Silk Girl: A Memoir of Love, Imprisonment and Protest, published in 2024 by Heyday Press. Her parents were U.S. citizens who were incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz.

“In 2018 protests erupted over the separation of families at the border. Because of my work with Topaz survivors who were children during WWII, the issue felt very personal to me. I created this piece for a protest against family separation at Lake Merritt in June 2018. It has since traveled to Dilley and Austin, TX; Ft. Sill, OK in 2019; and many local actions. The woman and boy dolls were added by Hilda Ramirez, a Guatemalan woman living in a sanctuary church in San Antonio with her son, to symbolize their plight.”

-Ruth Sasaki, Topaz Stories editor.

Resistance also comes in the form using the lessons of WWII incarceration to support reparations for Black Americans.