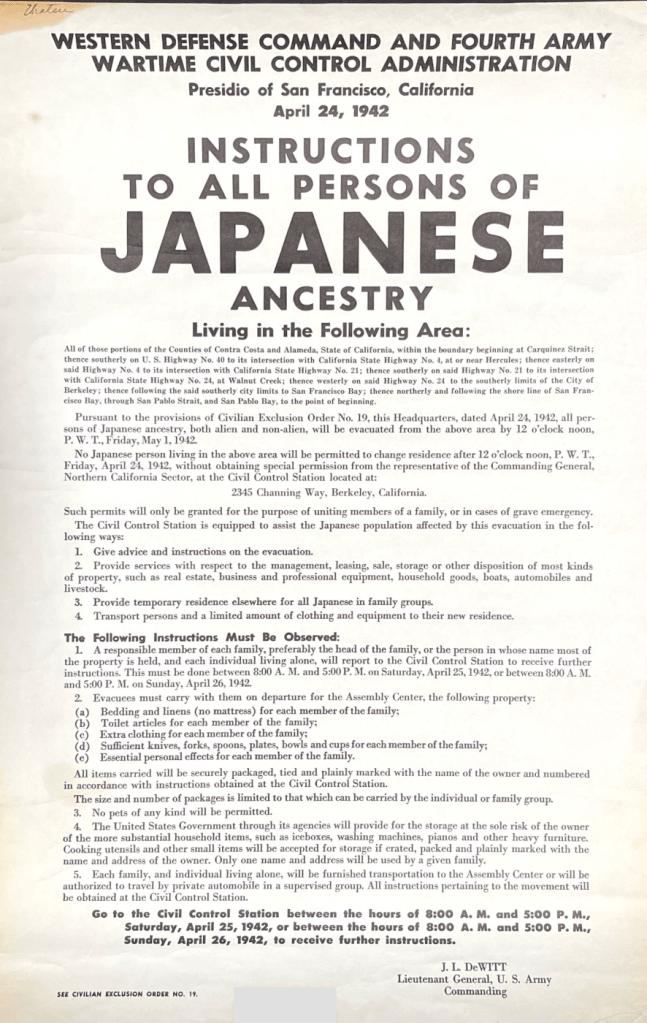

On February 19, 1942, in reaction to Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Guam, the Philippines, and Wake Island the previous December, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066.

Executive Order 9066 authorized the United States government to forcibly remove and incarcerate 40,000 immigrants and 70,000 American-born citizens from their communities. About 1,200 Berkeleyans were among those targeted.

Executive Order 9066 set off widespread panic among Japanese American communities along the West Coast. College students moved home; extended families moved inland or crowded into small homes in order to be together. Little detail was given about what would happen next, and many feared being separated from their families.

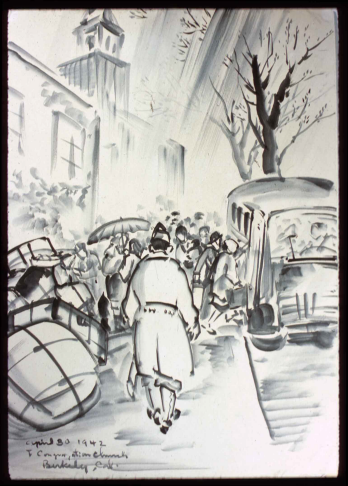

When the order came on April 11 for all Nikkei living in Berkeley to register for relocation, due to a last-minute effort – instead of being assigned to a parking lot – they were registered at and evacuated from First Congregational Church, Berkeley, where they found shelter, refreshments, and homes for pets, bonsai, even family-member’s ashes. But all but a few possessions were left behind, and the stark realities of Tanforan and Topaz lay ahead.

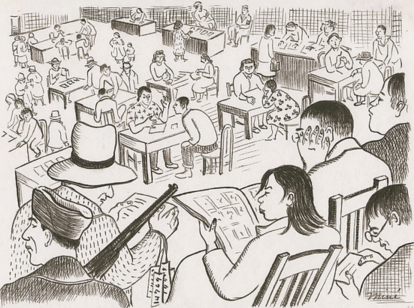

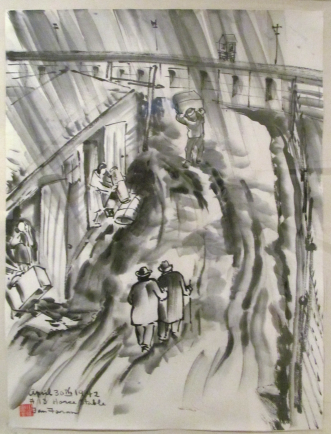

from Citizen 13660 by Miné Okubo.

Berkeley, California, 1942

from Citizen 13660 by Miné Okubo.

Japanese Americans in Berkeley were ordered to appear at the First Congregational Church at 2345 Channing Way, Berkeley, between April 25, 1942 and May 1, 1942.

Two Berkeley artists, Miné Okubo (above) and Chiura Obata (left), captured the sense of loss and chaos preceding the forced removal of over 1,000 Berkeley residents.

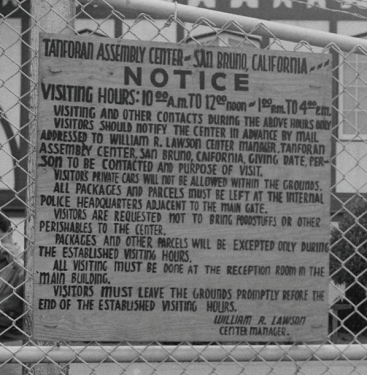

Tanforan

Japanese Americans who entered the camp system through Berkeley were first taken to the Tanforan Assembly Center. This “Assembly Center” was a hastily converted racetrack, where families crowded into barracks and horse stalls for seven months while the permanent incarceration camps were being built. The Tanforan Assembly Center was inhabited from April 28, 1942 – October 13, 1942.

In Tanforan, Japanese Americans worked to create a habitable living environment, organizing classes for schoolchildren, church meetings, entertainment, laundry services and barber shops. The conditions of Tanforan and the activities of those held there are documented in letters as well as in the Tanforan Totalizer, the newspaper produced in the assembly center.

Read a letter from Hiro Kitayama to Reverend Vere Loper of the First Congregational Church of Berkeley, May 17, 1942.

Dear Dr. Loper,

Greetings and salutations from Tanforan where good “horses” about 8500 strong

exercise and go through the motions of thoroughbreds day after day – 17 days for me now. It has taken me just about that much time to readjust myself. At first I didn’t think I could ever be contented here – contented in the sense of making the best of a bad situation. However, time seems to be the ever-efficient doctor. Seeing everyone round about go about their new lives with vigor and energy has buoyed my once dissatisfied nature. I am considering my previous experiences in recreational guidance, for some unknown reason I have been made the

supervisor of Sunday Schools for the whole camp, and also I’m assisting in the realization of an educational program at the earliest possible time. Already we have managed to get a Mr.Kirkpatrick from the Oakland Educational system to supervises our efforts. However, it is needless to say many of the activities are disorganized, requiring more efficient handling and management. Already we hear jibes of politics among our own people hiring and firing people, getting good jobs, trying to run the camp, etc. It is shameful but perhaps time again will be the

good healer.

After 17 days the food has improved manyfold. Our only complaint is it is yet inadequate– our helpings do not as yet fill the depths of our enlarged tummies. We dine at what they call the main mess hall along with 2000 other people for two weeks under such a condition it is understandable how difficult food preparation, cleanliness, adequate diet, etc. are to maintain. It was during this particular period that I thought the basis of my life dropped out. Perhaps if such conditions prevailed much longer as far as I was concerned I might have been whipped. Fortunately our sectional unit mess hall opened which feeds only 400 in our particular section. The cook is a former caterer from San Francisco. Just recently he was released from Missoula Montana along with Mr. D. T. Uchida. Therefore the cook, Mr. Kimura, appreciates the value of good food in camp. He does surprisingly well with the ingredients he is given to prepare. Our unit kitchen is classed as the best and tastiest among the seven other units scattered about the

117 acres. Unfortunately, some units are not ready to open which makes it necessary for some 4000 to eat together in the main mess hall where poor food, poor sanitary conditions, poor service prevails. I am certain in time this too will be improved.

Among our vital statistics, there have been two births here in camp that I know of – it is rumored there are five in all. There have been two deaths about which I know. Epidemics of German measles, mumps, have been going around since camp opened. The few doctors here are overtaxed with cases. As yet the hospital facilities are inadequate but rapidly taking on the appearance of a well-equipped hospital tho’ a barrack is being used for the patients.

The first day I arrived my family and I were taken to 83-4 which is room for four in a five-room barrack. The rooms are 20′ x 20′. There are five of us in this room, all we were given were five cots and five hay tick mattresses. Since then we have built 2 desks (my [besidie’s? illegible] and my own), a bookcase, a series of shelves for our clothing, a closet for our suits, coats, etc. three benches. The lack of good wood prevents me from further building at this time. I drowned my sorrows in carpenter work for about two weeks along with my other activities. Now I can

boast of my accomplishments. Incidentally, I am very grateful that we landed in a barrack rather than a horse stall. Perhaps you already know all about them so I will not write further about them. Suffice it to say the government made a big mistake sending evacuees here before work was completed.

Dr. Loper, I want you and your staff members to know this letter is written to you by one with a very thankful heart for all you have done for us all.

Yours truly,

Hiro Kitayama

Mother thanks you very much for caring for Dad’s ashes

Read the Tanforan Totalizer, July 11, 1942.

Topaz

In the fall of 1942, most Japanese Americans incarcerated at Tanforan were taken to Topaz, Utah, by train. Topaz was one of eight War Relocation Authority (WRA) Relocation Centers. Those incarcerees considered “high risk” were instead taking to higher-security Justice Department or U.S. Army facilities.

In 1943, many incarcerees were moved to other camps as a result of their answers on a loyalty questionnaire distributed by the WRA. Tule Lake became a higher-security incarceration camp where those considered disloyal were sent.

Read the Topaz Times, March 30, 1943

Relocation Centers were located in harsh, isolated places. In Topaz, incarcerees endured frequent dust storms, high heat, and snow during the winter.

SFMoMA. By George Matsusaburo Hibi. Used with permission

concentration camp, Utah

Mas Nakata (b. 1918, Alameda, CA) attended Everett Elementary School,

Alameda High School, and U.C. Berkeley. Incarcerated at Topaz, he

was released to New York City, where

he trained as a dental technician (1943), was drafted (1944) into 442nd

Regimental Combat Team, attended

MIS training and shipped to the

Philippines and Japan, returning to

California in 1984.

He made this replica barrack for Buena Vista Methodist Church’s Day of Remembrance (date unknown). The replica barrack was loaned to the Berkeley Historical Society and Museum from Berkeley United Methodist Church for the length of the exhibit, thanks to Rev. Mike Yoshii, Buena Vista Methodist Church, Alameda.

Nakata’s replica barrack shows a small, crowded room that was shared by a family. Rooms measured approximately twenty by twenty-five feet for a family of six. Incarcerees sewed privacy curtains and constructed furniture to make the rooms more comfortable. Bathrooms and dining areas were shared with many other families.

The Japanese Americans incarcerated at Topaz and the other incarceration camps were surrounded at all times by a barbed wire fence.

This barbed wire was stretched across the main entrance of the Topaz prison camp to keep the inmates confined from 1942-1945. It was cut down on July 5, 1989 and taken to Toru Saito’s home in Berkeley, where it rests today.

Toru Saito has lived in Berkeley since 1955 and loaned the barbed wire to BHSM for the duration of the exhibit.

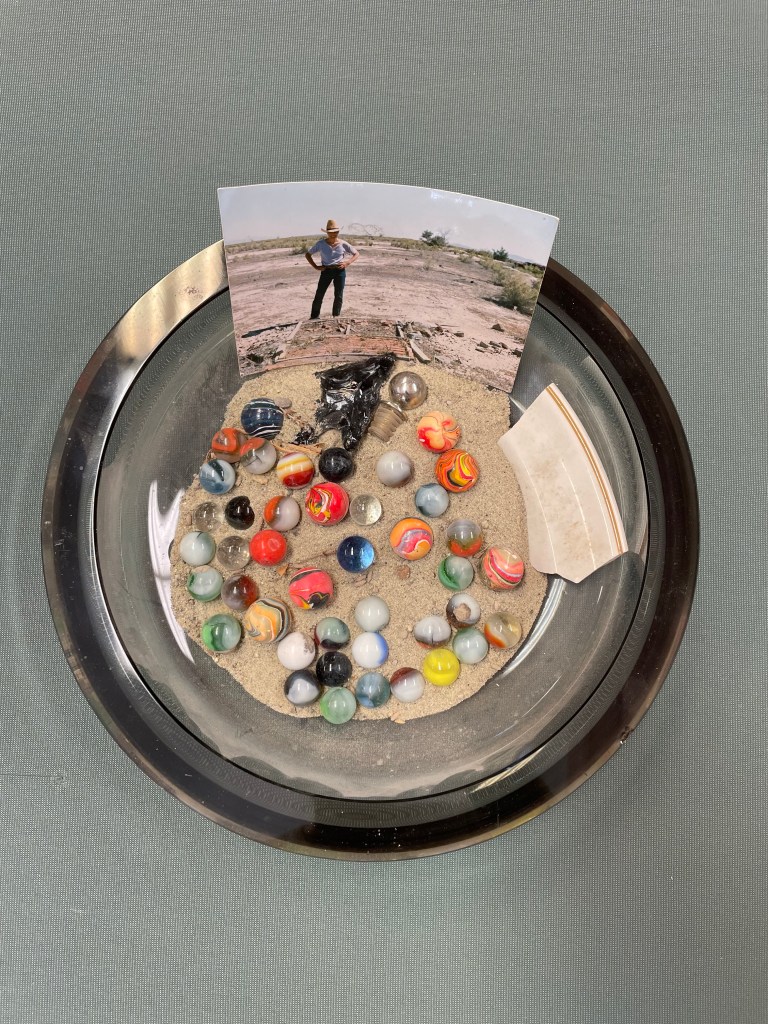

“These marbles were hidden in my secret hiding place, under the porch of Block 4, Barrack 10, Unit C and D. In our haste to escape the confines of the prison, at 3 a.m., October 11, 1945, I forgot to gather and bring them home to San Francisco.

In 1995, 50 years after we left, I was standing in front of our barrack – in front of our front porch… and something told me to dig at the lower right hand corner of our porch. So I took a stone and … I dug down there about eight inches, and I found 26 marbles that I had left behind under the porch that was my hiding place.”

–Toru Saito, who was incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz, 1942-1945, from the age of three years.

Witnesses and Advocates

Bay Area residents witnessed the removal of their Japanese American neighbors and friends and reacted in different ways. While many believed that the incarceration was a necessary wartime procedure, others were horrified by the swift removal of Japanese Americans. Many children who grew up in or near Japanese American neighborhoods still remember the day that their playmates were taken away.

Ruth Kingman

In 1942, Ruth Kingman was a member of First Congregational Church of Berkeley. When she and her husband Harry, a former New York Yankee, were missionaries in Asia, they helped introduce baseball to Japan. Harry was director of Stiles Hall, UC Berkeley’s YMCA, and Ruth was its unofficial hostess.

Both Kingmans strongly opposed the removal and incarceration of West Coast Nikkei. Ruth helped persuade the First Congregational Church of Berkeley to provide hospitality and a safe, indoor space for their registration and evacuation to the Tanforan Assembly Center.

In early 1943, Ruth Kingman became executive secretary of the Berkeley-based Pacific Coast Committee on American Principles and Fair Play, supporting Nikkei civil rights. Committee members included Robert Gordon Sproul and Dorothea Lange and her husband, Cal economics professor Paul Taylor.

Ruth wrote op-eds and often spoke both in person and on the radio and made two lobbying trips to Washington D.C. She and Anna Roosevelt even hung stark paintings of camp life by Chiura Obata on White House walls. Obata cited their efforts as a key reason for his 1945 decision to return to Berkeley.

Representative Ron Dellums

representative in Congress from the Ninth District of California.

Rep. Ron Dellums’ speech on Sept. 17, 1987, before the U.S. House of Representatives, arguing for what would become the Civil Liberties Act of 1988:

“Mr. Chairman, I appreciate the pleas to go home, but we’re here to do business, and this gentleman does not speak on the floor every day, on every issue. And there are few issues I might say to my distinguished friend from Massachusetts that are compelling enough that one must speak.

“Just introducing a few written remarks by the staff is not adequate. And making a few comments with respect to one of my colleagues’ amendments is not adequate.

“There comes a moment when one has to speak to tell his or her own story, vis-à-vis the proposition that is before the body. One of my distinguished colleagues on the other side of the aisle stated that he was born in 1942 and has no recollection of the war. This gentleman was born in 1935, so I do recall the war and felt the war through the body of a child and saw it through the eyes of a child.

“My home was in the middle of the block on Wood Street in West Oakland. On the corner was a small grocery store owned by Japanese people. My best friend was Roland, a young Japanese child. Same age. I will never forget, Mr. Chairman, never forget, because the moment is burned indelibly upon this child’s memory; six years of age. The day the Bekins trucks came to pick up my friend.

“I will never forget the vision of fear in the eyes of Roland, my friend, and the pain of leaving home. My mother, as bright as she was, try as she may, could not explain to me why my friend was being taken away as he screamed not to go. And this six-year-old black American child screamed back, ‘Don’t take my friend.’

“No one could help me understand that. No one, Mr. Chairman. So it wasn’t just Japanese Americans who felt the emotion, because they lived in the total context of the community. And I was one of the people who lived in the community.

“And so I would say to my colleague, this is not just compensation for being interned. How do you compensate Roland six years of age, who felt the fear that he was leaving his home, his community, his friend Ron the black American who later became a member of Congress; Roland, the Japanese American who later became a doctor, a great healer. “This meager $20,000 is also compensation for the pain and the agony that he felt, and that his family felt. This meager $20,000, in 1942 terms $2,800, is also compensation for the thousands of dollars of personal belongings that were strewn on the streets on 10th and Wood Street in West Oakland in 1942, because in case you don’t know it, they could only take what they could carry.

“And so the little football that we played with in the streets [was thrown away] in the streets. The games that we played that took up hours of our time: in the streets. The furniture that we romped on and wrassled upon as children in 1942: in the streets. So there’s $20,000 in this formula that if you are in for one day, you get a few nickels. If you’re in for three years, you get the whole $20,000. As if we could play that game.

“This is not about how long you were in prison. It is about how much pain was inflicted upon thousands of American people who happen to be yellow in terms of skin color, Japanese in terms of ancestry. But this Black American cries out as loudly as my Asian American brothers and sisters on this issue. So this formula, while well-intended, does not in any way address the reality of the misery, Mr. Chairman.

“It must be rejected out of hand because it doesn’t address the misery. Vote for this bill without this amendment and let Roland feel that you understood the pain in his eyes and the sorrow in his heart as he rode away screaming, not knowing when and if he would ever return.”

Ron Dellums represented Berkeley in Congress from 1971 to 1998.

Richard Allen

Richard Allen (b. 1933 in Berkeley General Hospital)

Richard’s father was a porter for the Southern Pacific, and his mother was a homemaker who greeted neighbors from the kitchen window as they walked to catch the No. 3 streetcar on Grove St. He taught English at Berkeley High School for several decades.

Richard played with his Japanese American friends on Grant and Stuart streets. The Uchida family, whose daughter, Yoshiko, would decades later become a famous children’s author, lived nearby.

In the spring of 1942 Richard learned that his Japanese American playmates were going to be taken away. “I remember a mother—I don’t know who it was—brought her two kids” to the front door. She said, “I have some toys that I’d like to give you. We have to go away.” She had a wagon full of toys.

“That was very sad for me. My mother said yes. But it was this horrible thing that I experienced. All my friends were taken away. All my Japanese friends. That was very momentous for me.” This was the first time he became aware of racial difference, he said.

Memories of that day still bring tears to his eyes.

Wayne Collins

Wayne Mortimer Collins was the “refined, intense civil rights atorney from San Francisco, smoking incessantly”* who defended Japanese American rights on a pro bono basis during the 1940s on behalf of the Northern California Branch of the ACLU. Among other important legal actions, he took on Fred Korematsu’s case, challenging the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, and the “Tokyo Rose” case, defending Iva Toguri, falsely charged with treason. Both were ultimately exonerated.

Collins’ greatest victory was in the “renunciant” case, involving 5000 people at the Tule Lake camp who renounced their American citizenship to protest the violation of their civil rights and the harsh conditions at Tule Lake. Collins kept them from being deported, and 23 years later won back American citizenship for virtually all of them. Several Berkeley residents and former UC Berkeley students were plaintiffs in this case.

Well-regarded author and former renunciant Hiroshi Kashiwagi (quoted above*) dedicated his memoir to “the memory of Wayne M. Collins who rescued me as an American and restored my faith in America.”