Berkeley’s Redlining and Exclusionary Policies

Amid widespread racial discrimination, both pre– and post–World War II, Berkeley’s Japanese American residents were victimized by restrictive covenants: provisions attached to deeds prohibiting the sale or rental of properties to Asians, Blacks, and other minorities. In the early twentieth century, influential Berkeley realtors like Duncan McDuffie strongly advocated applying the covenants to many of the city’s wealthier neighborhoods. Even in cases where wealthier neighborhoods did not have explicit covenants, realtors often refused to show homes to people of color. Further restricting Japanese Americans’ ability to buy homes in “desirable” neighborhoods were racist laws and hiring practices that constrained their ability to build wealth.

” It seemed the realtors of the area had drawn an invisible line through the city and agreed among themselves not to rent or sell homes above that line to Asians.”

– Yoshiko Uchida, Desert Exile

California’s Alien Land Law, enacted in 1913, denied Japanese immigrants the right to buy property. The law was not repealed until the 1950s. Japanese immigrants who did buy property were able to do so by putting the home in the name of an American-born child, neighbor, or friend. The vast majority of Japanese Americans before the war rented their homes.

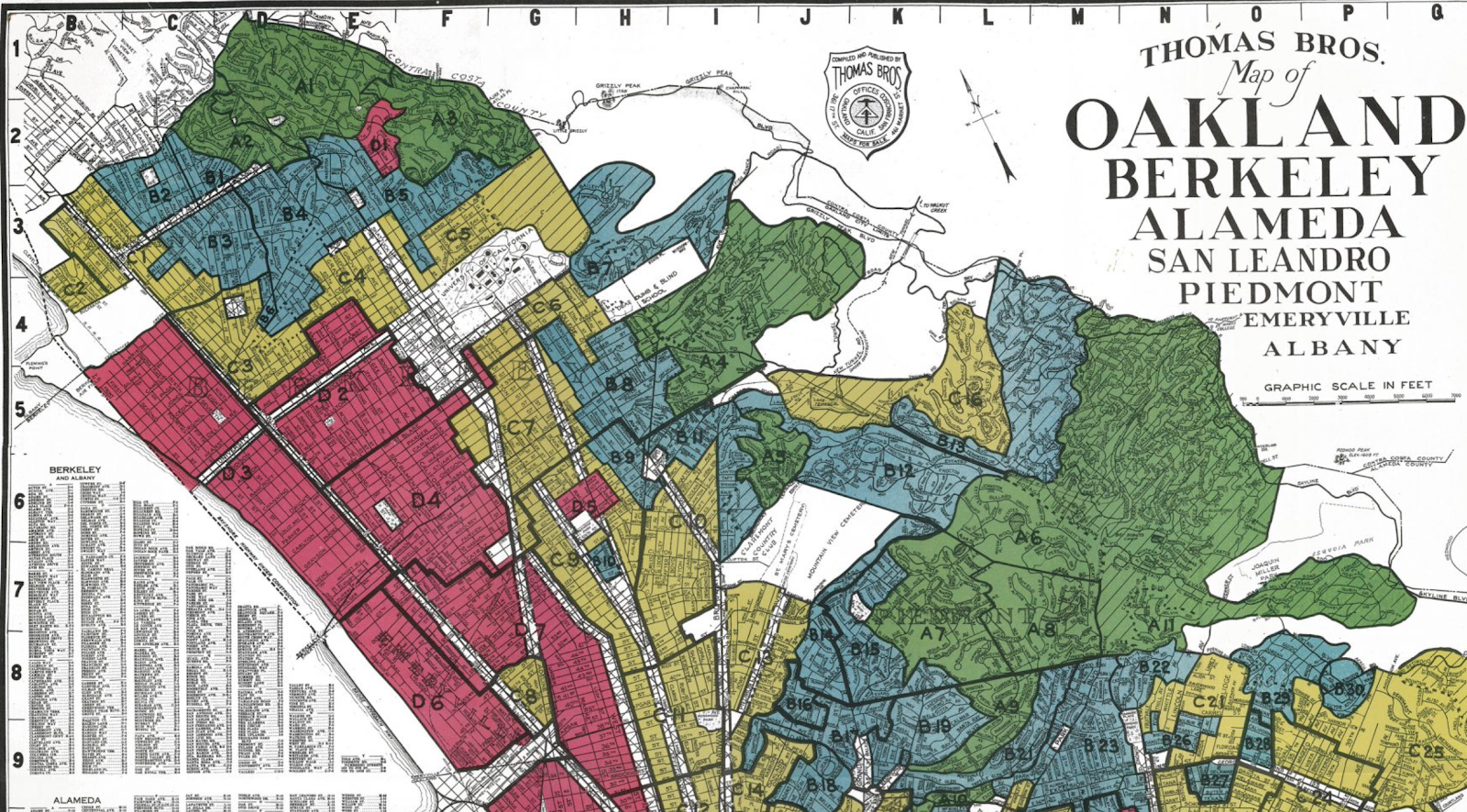

In the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was founded to help Americans buy homes in the wake of the Depression. As part of HOLC’s work informing banks on the probability of loan fails, the agency drew maps of hundreds of cities across the country, dividing areas into “best,” “desirable,” “declining,” or “worst.” Neighborhoods with high numbers of Black or Asian residents automatically received the “worst” rating, their neighborhoods shaded in red. The map above shows that large swaths of West and South Berkeley were considered “red”. This practice, referred to as redlining, made it difficult to obtain mortgages in integrated settings.

Redlining persisted because it resulted from a combination of federal, state, and local policy; banking practices; and informal agreements within the real estate profession. Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the enforcement of restrictive covenants in 1948, housing segregation continued through informal action by real estate agents and property owners, who continued to consult redlining maps and often refused to consider selling to non-white customers. The effect of these policies was to limit Asian and Black buyers to homes in the Berkeley flatlands, especially south of Dwight Way and west of Grove St. (now Martin Luther King Jr. Way). Some were able to gain access to home ownership outside of specific neighborhoods through sympathetic establishment realtors or through the growing number of non-white realtors, discussed below.

Here Lived draws from 1940 census data and shows where Japanese Americans lived before being forcibly removed and incarcerated during WWII. Most were renters. Some lived outside of the redlined areas due to employment or school.

CLICK TO READ MORE: Arlene Makita-Acuña’s Neighborhood

Our redlined neighborhood lay west of Grove, south of Dwight, north of Ashby, and east of San Pablo. This was the area to which non-Caucasians were restricted in Berkeley both before and after WWII due to realtors’, bankers’, and insurance agents’ written and unwritten agreements.

In the late ‘40s to mid-’50s when I was growing up, it was a comfortable neighborhood.

I was born here just after my parents returned from internment at Amache. Ours was a very multicultural neighborhood, with a mixture of African Americans from Louisiana who had come up to work in the Oakland shipyards during WWII; many Asians, including other Japanese Americans returning from the WWII incarceration camps; and Korean Americans and Chinese Americans. There was a sprinkling of Whites.

My mother had a green thumb and was always planting vegetables with my father in our backyard…and wonderful fruit trees. I could walk to my school (Longfellow), and my mother and I walked to our church (Berkeley Free Methodist on Derby near Sacramento).

We knew so many neighbors…of all shapes, sizes, and colors: the Nakanos two blocks away; our family doctor, Dr. Uyeyama, around the corner, who made house calls, giving me those dreaded penicillin shots when I had tonsillitis; the Koide family, around another corner, who had a small, convenient grocery store with some Japanese food supplies and the occasional candy; and Dr. Hayashi, the renowned Japanese American dentist who worked out of his house on Stuart Street and was lauded for his skill at making his patients’ dentures.

Everything we needed was so very close by. It was comfortable.

Student Housing

As a result of widespread housing discrimination, Japanese American students attending the University of California at Berkeley were forced to find their own alternative housing while attending the university.

Beginning around 1923, the Japanese Women’s Student Club began raising funds to purchase a building at 2509 Hearst St., which would become the Japanese Women’s Clubhouse. In 1966 the building was sold, and proceeds were used to endow the Japanese Women Alumnae Scholarship Fund.

Before WWII, Kimi Kami, who was associated with the Berkeley Buddhist Temple, and her husband, Junichi Kami, ran a women’s student rooming house. They operated the facility from approximately 1935 or 1936 to 1938 at their house at 1919 Addison St., and then from 1938 to 1942 at their three-story house at 1813 University Ave.

The Kami family stayed on the bottom floor, and the top two floors were generally reserved for the female students. Yae (Kami) Yedlosky1, the third of six children, recalled a childhood that was noisy and busy with all the students in the home. After the war, the Kami house again hosted numerous families and students—first, as a place for families looking to resettle, and then as a boarding house for male UC Berkeley students.

Yehan Numata, a young UC Berkeley student from Japan, was instrumental in forming the University of California Japanese Students’ Club (JSC) and purchasing a building to house the students.

The JSC building was destroyed in the 1923 Berkeley fire, after which Numata and others helped raise money to rebuild the dorm, which later became known as Euclid Hall. Following his graduation, Yehan Numata returned to Japan and in 1934 formed Mitutoyo Corporation, which grew into one of the largest manufacturers of precision measuring equipment in the world.

Japanese American Realtors

“The first time I ever heard the word ‘redlining’ was from Hank Kuwada at one of the sales staff meetings. He said, ‘You young guys, you’re going to have it easy from now on, because we could start selling homes to minorities north of Dwight Way.’”

Jim Furuichi

The existence of Japanese American and other non-white realtors helped to change discriminatory housing practices. Guaranty Realty was the first Japanese American-owned real estate business in Berkeley, established by the 1920s. Sakaye “Soppy” Iwai, a pioneering businessman, joined the company in the 1920s. Although his career was interrupted by his incarceration in Topaz, Soppy was instrumental in connecting later generations of Japanese American realtors.

After the war, Soppy established a retail appliance business in Oakland. Then, in 1948, Soppy formed Associated Services Enterprise at 1853 Ashby Ave., where he established multiple businesses, including real estate, appliance, jewelry, and laundry businesses. Soppy also established a retail storefront at 2439 Grove St., which later became home to several Nisei-owned businesses, including Yamasaki Real Estate, Asa Fujie’s accounting office, and Tad Hirota’s insurance office. In the early 1970s, with Soppy’s help, the same building housed the first East Bay Japanese for Action (EBJA) senior services agency.

Frank Yamasaki grew up in the South Bay and was incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz during the war. After the war, he and his family moved to Berkeley, where he started working as a gardener and then, through his wife’s family (Kitano), he met Soppy Iwai and began working at the Iwai-owned Associated Services Enterprise at 1853 Ashby Ave.

With Soppy’s assistance, Frank was able to obtain his real estate license and, in 1954, he opened his own real estate and insurance office at 2439 Grove St., where he would later share the space with Tad Hirota’s insurance brokerage.

Tad Hirota was born in Oakland in 1918. After incarceration at Topaz and then military service in the U.S. Military Intelligence Service (MIS) in the Philippines during World War II, Tad returned with his family to Berkeley.

Upon settling in Berkeley, Tad became one of the founders of Western Pioneer Insurance, which was formed in response to racial prejudice that prevented Japanese Americans from obtaining insurance coverage from the established agencies. He later opened his own insurance office at 2439 Grove St, sharing space with Frank Yamasaki and later East Bay Japanese for Action (EBJA).

Jim Furuichi was born in San Jose and as a child was sent to the Heart Mountain concentration camp. Jim moved to Berkeley in 1964 after meeting Hank Kuwada, who had just opened Kuwada Realty at 1701 University Ave. According to Jim, with his early experience selling encyclopedias door to door, he was a natural fit at prospecting for customers.