- Jim Furuichi

- Ruth Hayashi

- Tad Hirota

- Jordan F. Hiratzka

- Yuji Ichioka

- Chizu Iiyama

- Miyoko Ito

- Sakaye “Soppy” Iwai

- Frank Kami

- Betty Nobue Kano

- Dennis Makishima

- Masamoto Nishimura , Joseph Nishimura

- Chiura Obata

- Miné Okubo

- Thomas Tamemasa Sagimori

- Minoru (Min) Sano

- Kay Sekimachi

- Reverend Naomi Southard

- Toyo Suyemoto

- Dr. Yoshiye Togasaki

- Yoshiko Uchida

- Dr. Hajime Uyeyama

- Frank Yamasaki

- George Yoshida

Jim Furuichi

Jim Furuichi was born in San Jose and as a child was sent to the Heart Mountain concentration camp from Los Altos, where he and his family were living in 1942. Following the War, Jim returned to Los Gatos where his family retained their home and worked in a South Bay manufacturing company in the early years of Silicon Valley.

Jim moved to Berkeley in 1964 after meeting Peter Kawakami, who introduced him to Hank Kuwada, who had just opened Kuwada Realty at 1701 University Ave. According to Jim, with his early experience selling encyclopedias door to door, he was a natural fit at prospecting for customers.

In his May 2024 interview with the Berkeley Historical Society (BHS), Jim spoke about redlining: “The first time I ever heard the word “redlining” was from Hank Kuwada at one of the sales staff meetings. He said, “You young guys, you’re going to have it easy from now on, because we could start selling homes to minorities north of Dwight Way.”

“And as far as the red lining [type] of rejection, I didn’t know what that was. So I sold properties north of Dwight Way. Well, I didn’t let it affect me. I kind of put my blinders on and I don’t care about the discrimination. Some of it was so blatant and others were so subtle and, you know, so quietly done. “

In that same BHS interview, Jim reflected on his camp experiences: “Well, you know, this is one thing that I found out in talking to relatives and friends. And thank goodness there’s a common thread I found that runs through the elders in almost every family. “

“Whatever happened to us is in the past. Don’t let that bring you down. We’re here, we’re staying. We’re moving forward. We’re going to get educated. We’re going to get better.”

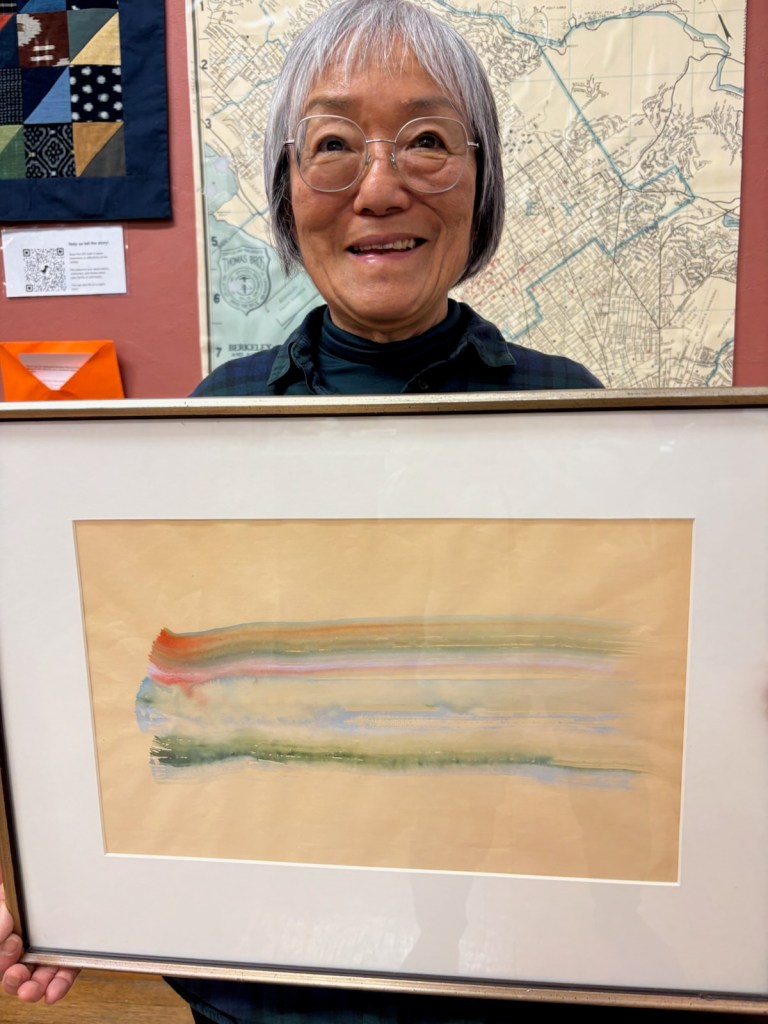

Ruth Hayashi

Ruth (Uyeda) Hayashi grew up in Berkeley and was incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz as a young girl. Before and after the war, Ruth lived with her family in a home on the property of 1301 Oxford, where her parents worked for the Welker family. Her father, Gonrokuro Uyeda, fell ill shortly before the family was forced to move to Tanforan. Her mother, Teruyo Uyeda, was allowed to visit him in Livermore until he passed away, leaving Ruth alone in camp.

The Uyeda family were members of the Christian Layman Church, where Gonrokuro contributed to the church’s newsletters. After the war, Ruth and her mother returned to Berkeley. Thomas Matsuoka, an artist who also attended Christian Layman Church, befriended the family and painted their home at 1301 Oxford. Ruth later donated this painting to the Berkeley Historical Society and Museum, where it was on display for Roots, Removal and Resistance.

Ruth was an active community member and shared her experience of unjust incarceration widely, including in the oral history conducted by BHSM, above.

Tad Hirota

Tad Hirota was born in Oakland in 1918. His parents, Konoye and Masjiro Hirota, immigrated to the U.S. from Mie-ken, Japan. Tad grew up in a West Oakland community that at the time was a multiracial center of Japanese American as well as African American community life in Oakland. Tad attended McClymonds High School, where he was active in sports, playing both basketball and tennis. In the 1930s he became president of the Japanese American Athletic Union, an organization he later enthusiastically supported for the youth in the Bay Area Japanese American community.

In 1936, Tad joined the newly emergent Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) as one of its founding members. JACL members in 1942 included other prominent Berkeley individuals Masuji Fujii, Frank and Toshiko (Tish) Yamasaki, Albert and Ruth Kosakura, George and Bess Yasukochi, and Mas Yonemura.

After incarceration at Topaz and then military service in the U.S. Military Intelligence Service (MIS) in the Philippines during World War II, Tad returned with his wife Hisa (June) to Berkeley, where they raised their children: Patty, David, and Sherry. Upon settling in Berkeley, Tad became one of the founders of Western Pioneer Insurance, which was formed in response to racial prejudice that prevented Japanese Americans from obtaining insurance coverage from the established agencies. He later opened his own insurance office at 2439 Grove St, sharing space with Frank Yamasaki and later East Bay Japanese for Action (EBJA).

Tad, along with other prominent Berkeley Nisei such as Frank Yamasaki, embodied the spirit of community service, playing an active role in the Berkeley Lions Club and co-founding the Berkeley-Sakai Sister City Program with Shigero Jio, Frank Yamasaki, William Porter, and others.

Jordan F. Hiratzka

Jordan F. Hiratzka established Berkeley Troop/Post 26 in 1950 at the young age of 26. A Nisei born in Santa Maria, CA, he was imprisoned at Gila River Concentration Camp in Arizona, served in the United States Military Intelligence Service and then graduated from the University Of California.

He served as Scoutmaster for almost four decades, and with his wife Maru, raised a family in Berkeley for over half a century.

As Scoutmaster, Hiratzka taught many generations life-long values like survival skills, leadership, recognition for hard work and the importance of community camaraderie. Hiratzka left a lasting, positive mark on us growing up in the ‘50s and ‘60s, up into the ‘90s.

Written by Gary Tominaga

Yuji Ichioka

Yuji Ichioka (1936-2002) was a political leader, activist, and scholar during the Third World Liberation Front movement in the late 1960s. Along with other activists, including his later wife, Emma Gee, Ichioka founded the student organization Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) at UC Berkeley. The creation of the AAPA, as well as Ichioka and Gee’s new term, “Asian American,” was the birth of the Asian American movement. This new movement united people of different Asian descent groups for common goals.

The Alliance was integral to the Third World Liberation Front protests which demanded that more faculty of color be hired and curriculum broadened to include the experiences of Black Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and Asian Americans.

Gee and Ichioka’s home at 2005 Hearst Avenue in Berkeley is recognized as the birthplace of the Asian American Movement and is a historic landmark. Gee and Ichioka went on to have distinguished academic careers. Ichioka wrote the seminal work The Issei: The World of the First Generation Japanese immigrants, 1885-1924.

The Ichioka family was incarcerated at Topaz and returned to California after their release to start a new life in Berkeley. Yuji Ichioka graduated Berkeley High School in 1954.

Chizu Iiyama

Chizu Iiyama was a lifelong political activist. She demonstrated for civil rights, protested the Vietnam and Iraq wars and in 1994 co-sponsored a successful national JACL resolution to support same-sex marriage. She spoke against nuclear weapons at an atomic bombing commemoration in Hiroshima.

In 1942, her family was forced to leave in April, before her graduation from U.C. Berkeley. Japanese American students were given C’s for leaving early but

at least Chizu received her diploma, in a horse stall at the Santa Anita racetrack before transfer to Topaz. U.C. Berkeley acknowledged this injustice in 1992, when 100 Japanese Americans in the class of ’42 were recognized. In 2009, Iiyama gave the acceptance speech when honorary degrees were granted to 500 whose education had been interrupted.

Chizu pushed for camp redress and often spoke with her husband Ernie about the camps at schools, including Cal. She and her daughter Patti picketed Woolworth’s on Shattuck Avenue for refusing to serve African Americans at lunch counters in the South and to hire them here. She organized the effort for a documentary on local Nikkei flower growers that is now a permanent feature at the Rosie the Riveter Museum in Richmond.

Miyoko Ito

Miyoko Ito (1918-1983) was a renowned painter. She was born in Berkeley, but her family moved back to Japan in 1923. When the Itos returned to Berkeley, Miyoko attended Berkeley High and UC Berkeley, where she earned a degree in art. She was incarcerated shortly before her graduation at Tanforan and Topaz, where she received her diploma behind barbed wire. Alongside other incarcerated artists, Miyoko taught art classes in camp.

Miyoko obtained permission to leave camp early, a year into incarceration, in order to attend a graduate program at Smith College. She then moved to Chicago in 1944, attending the School of the Art Institute, and settled in Chicago for the rest of her life. She became known for her abstract watercolor and oil paintings. Her art has been collected by and displayed across the country, including at the Smithsonian, BAMPFA, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Sakaye “Soppy” Iwai

Sakaye Iwai was a pioneering second-generation (Nisei) Japanese American businessman born in Berkeley in 1904. His father, Hideaki Iwai (b. 1867), along with Tadayori Wasa (b. 1866) and Rin Wasa (b. 1876), in 1905 established the Nippon Laundry business at 2034 Addison St. (formerly home to Stadium Garage and currently home to Freight and Salvage).

Sakaye (known as Soppy) attended UC Berkeley from 1926 to 1930. His two older sisters, May (b. 1899) and Sei (b. 1903) graduated from UC Berkeley in 1924 (May) and 1927 (Sei).

In the 1920s, Soppy joined one of Berkeley’s first Japanese American–owned real estate businesses, Guaranty Realty, which provided him with the means to own and purchase real estate. This success allowed him in later years to help other Japanese Americans establish their own businesses. When World War II broke out, Soppy and his family were sent to Topaz Relocation Camp in Utah.

After the war, Soppy returned to Berkeley and with a partner, Susumu Yamashita, established a retail appliance business in Oakland (at 825 Market St.). Then, in 1948, Soppy formed Associated Services Enterprise at 1853 Ashby Ave., where he established multiple businesses, including real estate, appliance, jewelry, and laundry businesses. Susumu and Frank Yamasaki ran the appliance sales. Susumu Yamashita would, in 1951, move to New York to open the first post-war office of the Mitsubishi Corporation.

Soppy also established a retail storefront at 2439 Grove St., which later became home to Nisei-owned businesses, including Yamasaki Real Estate, Asa Fujie’s accounting office, and Tad Hirota’s insurance office. In the early 1970s, with Soppy’s help, the same building housed the first East Bay Japanese for Action (EBJA) senior services agency.

Soppy Iwai is listed in the “Here Lived” database at 2034 Addison St.

Frank Kami

Frank Kami was born and raised in Berkeley, and attended Whittier Elementary School, Garfield Middle School, and Berkeley High School. His family was incarcerated in Topaz when Frank was a junior at Berkeley High, soon after he had started dating Miyoko Akimoto, who would later become his wife. The two were separated during the war, but managed to find each other again, a story that Frank shared and wrote about throughout his life.

The Kami family was one of the few that still had a car in April 1942 when the removal to Tanforan was taking place. Dr Kami recalled driving around Berkeley, picking up people and their luggage because they had no transportation to the church. At Topaz, he made furniture which is on display in the Topaz Museum in Delta.

After he graduated from high school, Frank enlisted and served in Germany. He then attended UC Berkeley, where he reunited with Miyoko. The couple married and moved to Chicago, where Frank attended Marquette University Dental School. They later moved back to Berkeley, where Frank operated his own dental practice for many years. Frank also served as the president of the Berkeley Dental Association. He and his family lived on Summit Road, one of the few Japanese American families to live in the hills in the 1950s-1960s. He was able to purchase the land privately through the help of a white friend.

Dr. Frank Kami contributed to Topaz Stories, and his story can be found here: https://topazstories.com/frank-and-miyoko/

Nancy Ukai contributed to this biography.

Betty Nobue Kano

Betty Nobue Kano is an artist, teacher and activist. Born in Japan in 1944, Kano moved to California as a young child. She attended UC Berkeley during the 1960s, where she joined the Free Speech Movement.

After leaving UC Berkeley, Kano earned her Bachelor of Arts degree in painting at San Francisco State University in 1967, and completed her Master of Fine Arts degree at University of California, Berkeley, in 1978. While in Berkeley, Kano organized the Asian American Political Alliance and participated in Third World Liberation Front (TWLF).

Kano has taught in various places, including San Francisco State University. She has also helped to found the artist groups Asian American Women Artists Association, Resistance 500, and Women of Color Camp.

Dennis Makishima

Dennis Makishima is a third-generation (Sansei) born and raised in Berkeley in the 1950s and ‘60s. From his humble beginnings in the Sixth St. neighborhood of Berkeley, through a tour of duty in Vietnam, education at UC Berkeley, and work at the Produce Center market during the creation of the Gourmet Ghetto, Dennis serendipitously fell into a career as an internationally known aesthetic tree pruner.

In his recently published memoir Mr. Omoshiroi (“omoshiroi” is translated as “interesting” in English), Dennis tells his story in his own way: “I was born in a foreign country: Berkeley, California. I am proud to be a Berzerklian. When I travel, and people talk bad about Berkeley, bring it on.”

On his work, Makishima says: “When I started aesthetic pruning, I knew nothing about trees, arboricultural rules, and pruning techniques. I relied on common sense, logical thought, and observation… I am an aesthetic pruner of ornamental trees and shrubs. Ornamental is a size classification of a tree about the height of a single-story house. I emphasize horticulture, aesthetics, and common sense. I deal with urban issues such as tree scale, proportion, client desires, neighbor problems, fire abatement, sustainability, and living art.”

“In my career, aesthetic pruning was never a job. It was pure joy, happiness, simplicity, and a way of life. I successfully thrived in a 40-year career.”

Masamoto Nishimura , Joseph Nishimura

Masamoto Nishimura was born in Japan in 1895. In 1921, following high school, he moved to the U.S. to attend Northwest Nazarene College in Idaho. Free Methodist missionaries encouraged him to establish a church for Japanese people, which he did first in Arizona and then in New Mexico.

Masamoto attended the University of Southern California, where he received a master of divinity degree. He then moved to Berkeley and studied at the Pacific School of Religion.

In 1923, Masamoto founded the Berkeley Free Methodist Church. Church meetings were first held in private homes and then at the church’s first permanent location on Dwight Way east of Shattuck. The church later moved to Derby St., where it existed through most of the 1980s.

Masamoto’s son, Joseph Nishimura, was born in Berkeley in 1933. He attended Berkeley High School and in January 1952 stayed at Euclid Hall (the Japanese Men’s Club) for one semester while attending UC Berkeley. Joseph then attended Princeton, from which he graduated in 1956. At that time, he was one of only a handful of Japanese and Japanese American students enrolled at Princeton.

Joseph enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was stationed in Sasebo, Japan, for three years. Following his discharge from the Navy, he enrolled in the Stanford School of Business, where he received his MBA in 1961.

After completing his degree, he joined one of the Big 8 accounting firms, Touche, Ross, Bailey & Smart, one of the few Japanese Americans hired into the company at that time. He retired after completing a successful twenty-five-year career in New York at Touche Ross.

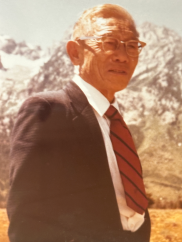

Chiura Obata

Chiura Obata (1885-1975) was a renowned artist and UC Berkeley professor. Born in Japan, Chiura settled in San Francisco in 1903. He married noted Ikebana artist Haruko Kohashi in 1912. The couple had four children.

Chiura Obata’s work grew in prominence over the 1920s and 1930s, leading to several exhibitions and commissions in the Bay Area and internationally. Known in particular for his landscape paintings, Chiura was inspired by his exploration of California, especially Yosemite. In 1932, he became a lecturer of art at UC Berkeley, and was soon promoted to assistant professor. He also opened the Obata Art Studio in Berkeley, where he sold supplies and taught classes.

The Obata family was removed from Berkeley in 1942 and incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz. The Obata Art Studio closed, and his paintings were stored by UC Berkeley president Robert Sproul. Chiura continued his teaching while incarcerated, creating the Topaz Art School. He documented his time in the camps through his art.

The Obatas received permission to leave Topaz in 1943 following an assault on Chiura. They resettled in St Louis, where one of his sons was attending school. Chiura and Haruko returned to Berkeley in 1945, and Chiura was reinstated as a professor at UC Berkeley.

Miné Okubo

Miné Okubo (1912-2001) was a renowned artist who documented her incarceration through drawing, notably in her book, Citizen 13660. She was born in Riverside, California, one of seven children. Her mother, Miyo Okubo, was a graduate of the Tokyo Art Institute who instilled a love of art in her children.

Miné attended UC Berkeley, where she earned her Bachelor and Master’s degrees in Fine Art. She then worked for the Federal Art Project, a branch of the New Deal-era Works Progress Administration, followed by an artistic fellowship in Europe. When WWII broke out in Europe, Miné returned to Berkeley, where she moved in one of her brothers, Toku Robert Okubo, on Berkeley Way. Her family was incarcerated across several different camps as they had been living in different parts of California when Executive Order 9066 was issued.

Miné and Toku were incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz. There, she taught art classes as part of the Topaz Art School, led by Professor Chiura Obata. Miné’s detailed drawings of life in camp gained publicity when she entered them into Bay Area art shows from her imprisonment. The magazine Fortune created a special issue focused on the art of Okubo as well as her contemporaries also in incarceration camps, Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Taro Yashima. The three artists’ work was also exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Art.

Miné was able to leave Topaz in 1944, and settled in New York City, where she lived until her death in 2001. Alongside her art, Miné is remembered for her lifelong activism. She used her drawings to demonstrate the injustice of Japanese American incarceration, later turning a selection of these drawings into the book Citizen 13660, which documents her experience in Tanforan and Topaz. She was an active voice in the movement for redress.

Thomas Tamemasa Sagimori

Thomas Tamemasa Sagimori (July 29, 1919–April 5, 1945) was born in Berkeley, the first son of Tamejiro Sagimori and Suye Kobun Sagimori, and lived at 2022 Dwight Way. His father came to the U.S. in 1916; his mother arrived in the spring of 1919. He attended Berkeley public schools and then UC Berkeley, majoring in forestry. Tom was social and popular and enjoyed camping in the Sierra with forestry classmates. He enlisted in the Army on July 7, 1941.

When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the U.S. entered the war, his family was ordered to Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno and then Topaz Relocation Center in Delta, Utah.

Though a college graduate, Tom’s rank was that of technical sergeant, and he served in Company L, 3d Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), attached to the 92nd Infantry Division. Tom fought in many European battles including the rescue of the Lost Battalion and the Battle of Bruyères. Shortly before the war ended, his company broke through a strategic foothold of the Gothic Line at Mt. Folgorito in Italy.

In 442nd Battlegrounds Revisited, Genro Kashiwa wrote: “First platoon was able to advance to the foot of the small peak at the top, situated at the end of a finger of the mountain range… First platoon’s advance was stalled by sniper fire from the hill opposite its position. Third platoon led by Sgt. Sagimori was attacking the hill from which the sniper fire was coming, starting from the bottom of the saddle below 1st platoon and following up a rock wall. Ordinarily that would have been safe, but in this situation, 3rd platoon was subject to sniper fire from the hill 1st platoon was trying to take.

“So instead of being safe, 1st and 3rd platoon were stalled being subject to cross fire from hills next to their respective objectives. We took casualties, Sgt. Sagimori was killed.”

Despite heavy enemy fire, Sagimori led his platoon to secure a ridge, and he killed four of the enemy. He then exposed himself further to atack a machine gun nest, throwing a grenade and killing one of the enemy and wounding another. In this action, Sergeant Sagimori was fatally wounded.

Sgt. Sagimori was awarded the Silver Star (posthumously) and Purple Heart for his bravery. He is buried at the family gravesite at Sunset View Cemetery in El Cerrito.

Minoru (Min) Sano

The late Mr. Min Sano was a star quarterback for the Lumpe Lions, and played at halftime in the 1935 Rose Bowl. He could have been a star quarterback for the University of California.

However, during his sophomore year at Cal, he was imprisoned in Tanforan and Topaz concentration camps. After World War II, he was a star quarterback for the University of Denver, where he met his dear wife Yae (Yaeko). He served in the United States Armed Forces. They settled in Berkeley and raised three children.

In 1957, he established the Berkeley Bears, whose motto was “It’s The Way You Play The Game That Counts,” and was respectfully known as Papa Bear. Multiple generations learned sportsmanship, teamwork, community camaraderie and baseball skills.

Kay Sekimachi

Kay Sekimachi is an internationally known, Berkeley-based fiber artist and weaver. She is known for her flat loom pieces as well as her three- dimensional sculptures using nylon monofilament. Sekimachi’s art is in collections in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Museum of Arts & Design in New York, the Oakland Museum of California, the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and others.

Born in San Francisco in 1926, Sekimachi grew up on Berkeley Way in a rented home with her widowed mother and two sisters. The artist Miné Okubo lived across the street. Like Okubo, Sekimachi was incarcerated with her family in Tanforan and Topaz in 1942. She was a Berkeley High School student. While incarcerated, she took art classes and expanded her skills in drawing and painting. After being released from camp, she settled in Berkeley and attended the California College of Arts and Crafts, where she studied between 1946 and 1949.

As part of Roots, Removal, and Resistance, BHSM conducted an oral history interview with Kay Sekimachi, which can be viewed below.

Reverend Naomi Southard

Reverend Dr. Naomi Southard was the first Japanese American woman to be to be Received into Full Connection in the United Methodist Church, and served as minister at Berkeley Methodist United Church (BMUC) from 1997 to 2018.

Reverend Southard was born in 1951 in San Francisco. She earned an MDiv degree from Harvard Divinity School in 1980, and a PhD from the Graduate Theological Union in 2004. Before entering her ministry at BMUC, she served at Lake Park United Methodist Church in Oakland, and as executive director at the National Federation of Asian American United Methodists.

Reverend Southard is a strong advocate for social justice. During her ministry at BMUC, she connected the church to the Reconciling Ministries Network, an organization which supports the full inclusion of all people regardless of sexual orientation, and introduced the Congregational Care Ministry, designed to help congregants during difficult times.

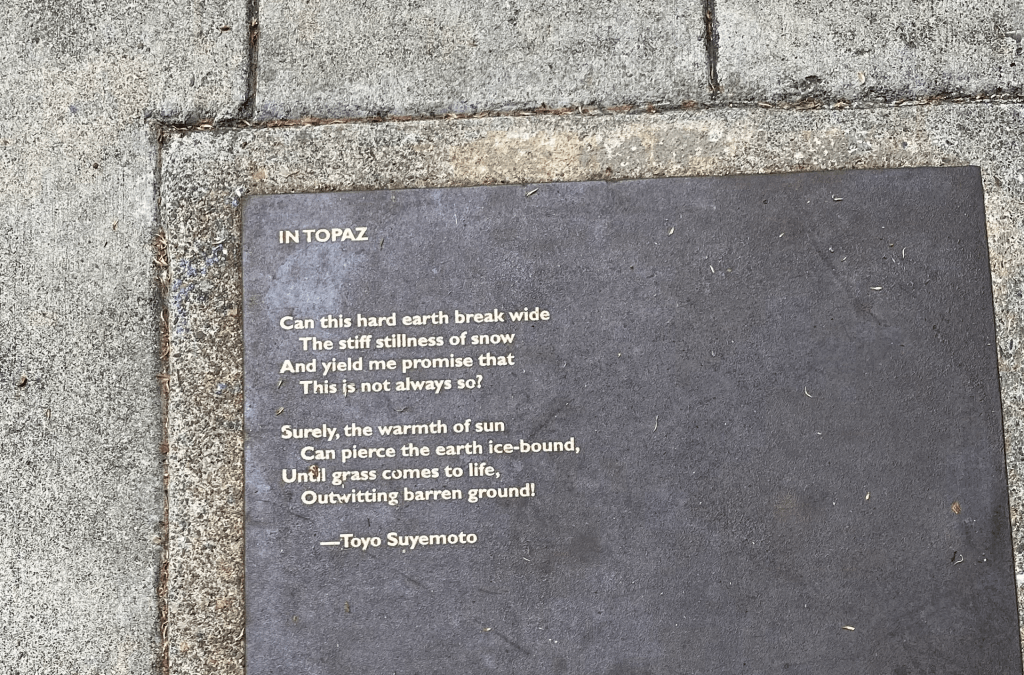

Toyo Suyemoto

Toyo Suyemoto (1916-2003) was a poet and librarian. Born in Oroville in 1916, she was interested in literature and poetry from an early age. Her work was published beginning in her teenage years in Japanese American community magazines and newspapers.

Suyemoto attended UC Berkeley, where she studied English. While incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz, she taught English and Latin, and worked in the camp library. After leaving the camp, she followed her family to Cincinnati. Her son, Kay, died in 1958 at age sixteen due to the poor conditions in Topaz, where he had spent much of his childhood. After Kay’s death, Suyemoto earned her Library Science degree at the University of Michigan. She became the Head of the Social Work Library and Assistant Head of the Education Library at the University of Ohio, where she worked until her retirement in 1985.

Suyemoto used her memories of Topaz to testify before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. She also spoke to public audiences at schools about her incarceration. Her poems were rediscovered later in life and after her death. Her memoir, I Call to Remembrance: Toyo Suyemoto’s Years of Internment was published posthumously in 2007. In Berkeley, pedestrians can find one of her poems on Addison Street along the Berkeley Arts District Poetry Walk.

Dr. Yoshiye Togasaki

Yoshiye Togasaki (1904-1999) was a physician and activist born in San Francisco to a large family of five sisters and three brothers. Dr. Togasaki and her five sisters all eventually became healthcare professionals.

Dr. Togasaki attended UC Berkeley, where she graduated in 1929 with a B.A. in Public Health. She maintained a life-long connection to the university as a founding member of the Japanese Women Alumnae of UC Berkeley. She later earned her MD from John Hopkins School of Medicine in 1935, and her MPH from Harvard in 1948.

Despite her impeccable academic record, Dr Togasaki struggled to find employment in public health in the pre-war years due to racism in the medical field. She was incarcerated at Manzanar, where she became a camp physician. During her time at Manzanar, she advocated for the health of the incarcerated population and worked to secure proper sewage systems, clean water, vaccinations, and supplies for babies. She was able to leave Manzanar early, in 1943, to pursue residency, and worked as a consultant for the United Nations to improve conditions at a refugee camp in Italy towards the end of WWII. For most of her career, she worked in the Contra Costa County Health Department.

Dr Togasaki’s lived experience as an incarcerated Japanese American, woman, and physician informed her activism. She was active in the redress movement and spoke at hearings on the Human Rights Act of 1985 and the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. She advocated on behalf of Planned Parenthood, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Japanese American Citizens League, and was recognized for her activism by the California Association of Mental Health, the JACL, Planned Parenthood, Contra Costa County, the Japanese Women Alumnae of UC Berkeley, the American Association of University Women, and the American Medical Women’s Association.

Yoshiko Uchida

Yoshiko Uchida (1921-1992) was a Berkeley-born, award-winning author of many children’s books, including several that explored the incarceration of Japanese Americans through a child’s perspective. She also published a memoir of her experience, titled Desert Exile, that documented her family’s experience of incarceration at Tanforan and Topaz.

Yoshiko Uchida was born in Berkeley and raised in a rented home on Stuart Street, just outside of the redlined neighborhood that most Japanese Americans lived in. The family attended the Japanese Independent Congregational Church of Oakland, and unlike most of their Nisei peers, Yoshiko and her sister Keiko did not attend Japanese language classes. Yoshiko attended Berkeley High and graduated early, enrolling in UC Berkeley at age 16, where she earned a degree in English, history, and philosophy.

Yoshiko’s father, Issei Dwight Takashi Uchida, was arrested shortly after Pearl Harbor. He was considered a threat due to his activities as a community leader among Japanese Americans, and because he maintained ties to Japanese colleagues who sometimes came to visit the Stuart Street home. During his detention, Yoshiko, Keiko, and their mother, Iku Umegaki Uchida, were forced to pack up their home and were taken to Tanforan, where Takashi eventually joined them. During the duration of her incarceration, Yoshiko taught at the camp school and participated in the Topaz Art School and in church activities.

Yoshiko was able to obtain permission to leave Topaz in May 1943, in order to attend Smith College, while Keiko secured a teaching position at Mount Holyoke College. The sisters eventually moved to New York City, where Yoshiko began her writing career in earnest. After spending some years in Japan, she returned to the Bay Area and lived in Berkeley until her death in 1992.

Dr. Hajime Uyeyama

More than 200 Berkeley and Oakland residents signed a petition at Tanforan with a simple request to the camp warden: “Please appoint Dr. Hajime Uyeyama to the staff. We have for the past 12 years depended upon his vital services and loyal interest to us.”

Dr. Uyeyama, a beloved Berkeley doctor, was appointed to the Tanforan staff but within weeks, in June 1942, he and his young family of four was transferred to the Tule Lake prison camp in northeast California for protesting Tanforan’s poor medical equipment and skimming in mess hall operations.

At Tule Lake, a report decried his “outspoken” manner. His refusal to accept low standards of medical treatment led to the family’s transfer to a third concentration camp, Amache in Colorado. There Uyeyama endured a chilly reception from Japanese American camp doctors. Inmates could choose their own doctor and Uyeyama was popular. His daughter, Lenore, said that a big fist fight erupted but that Uyeyama told her that he had wrestled at Cal so “I was able to take care of myself.” His patients at Amache loved him, she said.

In 1945, the family was released and Uyeyama restarted his practice at the office and family home at 2808 Grove Street. He made house calls in the morning and held office hours from 1 p.m. to 9 p.m., said Lenore, who spent three years of her childhood in the camps and often joined him on house calls.

He loved classical music and jazz, she said. “He would finish at 9 p.m., write up his records at 10 p.m., then go listen to Lionel Hampton and Dave Brubeck on Broadway in San Francisco.”

Hajime means “beginning” in Japanese. Hajime Uyeyama was the first boy born to Jitaro Uyeyama from Oita Prefecture and Tomiyo Nakagawa Uyeyama of Sendai City. Their first child, Kiyo, was born in Japan, in 1900. The young couple moved to California and had three more children in Berkeley: Hajime (1904), Kahn (1908) and Yo (1912). Jitaro’s successful career as a N.Y. Life insurance agent enabled the family to pay for higher education. Hajime and Kahn graduated from the University of California at San Francisco Medical School and became physicians and surgeons. Kiyo and Yo were among the first Japanese American women graduates of U.C. Berkeley.

Hajime’s first two years of medical study were spent at Cal, where he met Grace Chiyo Takata, a botanist who graduated Phi Beta Kappa. The couple married and had three children, all of whom went into medicine: Ronald Ronoru (cardiology); Lenore Setsuko (dermatology), and Irene Sachiko (rheumatology).

Dr. Uyeyama’s name frequently surfaced during research for this exhibition. As a U.S.-born citizen, he helped Kurasaburo Fujii, an immigrant, purchase a home. He delivered Arlene Makita at Herrick Hospital in 1946 after having met her parents at Amache. Richard Allen remembers walking by the Uyeyama office at 2808 Grove Street when he was a child, and Arlene remembers him making house calls to her family to care for her and give injections. Many people who appear in this exhibition signed the Tanforan petition: Tsugio Kubota, Chiura and Haruko Obata, Frank Tsukamoto, Juzaburo Furuzawa, Frank Seisaku Katayanagi. Dr. Uyeyama was 38 at the time. He died at age 79 in Berkeley, in 1983.

Frank Yamasaki

Frank Yamasaki grew up in the South Bay, where his parents had a farm in Mountain View. During the war years, Frank; his wife, Toshiko (Tish) Kitano-Yamasaki; and their five-year old daughter, Leiko Joan, were incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz.

After the war, the family moved to Berkeley, where he started working as a gardener and then, through his wife’s family (Kitano), he met Sakaye (Soppy) Iwai and began working at the Iwai-owned Associated Services Enterprise at 1853 Ashby Ave.

With Soppy’s assistance, Frank was able to obtain his real estate license and, in 1954, he opened his own real estate and insurance office at 2439 Grove St., where he would later share the space with Tad Hirota’s insurance brokerage. In the 1970s, this address would also house the first offices of East Bay Japanese for Action (EBJA).

Despite the rampant discrimination and segregated business practices of the time, Frank and his wife, Tish, were very civic minded, wanting to contribute to the city of Berkeley and its business and social community. From the 1950s, Frank worked to promote youth programs in the East Bay. His activities included founding the Downtown Merchants baseball team, a racially integrated youth team sponsored by the downtown Berkeley merchants.

He later also founded the primarily Japanese American East Bay Girls Athletic League (EBGAL). In 1958, Frank was vice president and then president of the Berkeley YMCA Central Y Men’s Club, a service organization that promoted equality and participation in civic life from members of all backgrounds, lifestyles, and religious beliefs.

Frank Yamasaki with Mayor Warren Widener’s sons, Sister City Day, ca. 1978, Berkeley Gazette.

In 1966 Frank, along with Tad Hirota and Shigeru Jio, helped found the Berkeley-Sakai Sister City Program. In the 1970s Frank was president of the Berkeley Lion’s Club. Other organizations of which Frank was a prominent member included the Berkeley Redevelopment Agency Board and the Berkeley Co-op Credit Union Board.

George Yoshida

George Yoshida was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1922 and spent his formative years in the 1930s listening to many of Seattle’s jazz musicians. In 1936 his parents relocated to East Los Angeles, and in 1942, after the outbreak of war, the family was incarcerated in Poston, Arizona. A year later, George was drafted and assigned to the Military Intelligence Language School at Ft. Snelling in Minnesota.

Even while imprisoned at Poston, George’s love of jazz persisted. In camp, he played alto saxophone for the Poston Music Makers and later did the same in the Ft. Snelling jazz band. George married Helen Furuyama in Chicago in 1945, and in 1946 George and Helen moved to Berkeley, later settling in nearby El Cerrito. In 1952, George received his teaching credential at UC Berkeley and began his 35-year teaching career at Washington Elementary School.

Elementary School, 1966, from

Reminiscing in Swingtime.

Fortuitously, for George, who documented his love of jazz in the 1997 book Reminiscing in Swingtime, Washington Elementary principal Herb Wong developed an innovative jazz education program, inviting such renowned jazz masters as Oscar Peterson, Louis Hayes, Roland Kirk, and Phil Woods to play at Washington Elementary School. That program would in later years become the impetus for the highly acclaimed Berkeley High Jazz program.

In his retirement years, George was a mentor to many Sansei musicians in the Asian American jazz scene, forming and directing the J-Town Jazz Ensemble and frequently playing with Asian American musicians Mark Izu and Anthony Brown at numerous events in support of Asian American music and culture in the Bay Area.